Part I By Guita G. Hourani

I. INTRODUCTION There are six well known saints with the name of Marina or Marinos – Marina the Monk (or Marina the Syrian), Marina the Martyr of Antioch, Marina of Spain, Marina of Alexandria, Marina of Sicily and Marina the Cistercian (Clugnet 1904: 564- 568). However, there are most likely two who have truly existed -- Marina of Antioch who accepted martyrdom for her faith and Marina the Monk who suffered the consequences of her imposture as a male monk in the Monastery of Qannoubine, Lebanon (Clugnet 1904: 568). Léon Clugnet states that the confusion pertaining to all of the other saints named Marina is due to the translators and the copyists’ attribution of the saint’s origins to their own countries or other countries that they felt better fit the Saint’s life. This is why we find that the Greek version of Saint Marina’s life places her birth in Bethany; the Coptic version in Egypt and some of the Latin places it in Italy (Clugnet 1904: 265 footnote # 2). According to the most ancient accounts on Saint Marina the Monk, only one place of origin could be hers -- Lebanon. Clugnet resolves that until new discoveries are made, the only origin of Saint Marina must be the one known to us according to tradition and since the only tradition about this Saint is found among the Maronites of Lebanon, then Lebanon is to be considered the land of her birth (Clugnet 1904: 565). The Maronites resolutely believe that Marina originated in Lebanon and that as a monk she has lived and died in the Monastery of Qannoubine in the Holy Valley of Qadisha. J. Fiey in turn concludes that Marina in question is truly a local saint of Lebanon, victim of imposture (Fiey 1978: 33).

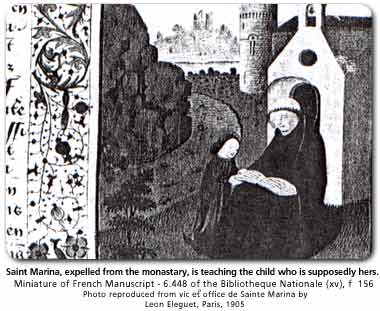

Monastic life in the fifth century was much more a cenobitic life, which is a communal ascetic life, than anchoretic, which is a solitary ascetic one. The Cenobetic monasteries had small but separate cells where the monks lived, this made it possible for Marina to conceal her identity. With her male name, short hair and clothes, but mostly with her ascetic living, which changed her body’s biology, hence made her lose much of her womanhood appearance and physical nature, Marina was able to go on living at the monastery with a disguising identity until her death. As to the century in which this Saint has lived, Clugnet agrees with F. Nau that it must be the fifth century since there were great details in her legend presented in the Syriac Manuscript Nº 30 dated 778 AD, folios 70r-76v of the Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai (Clugnet 1904: 565, 593). II. BIOGRAPHICAL RESOURCES The account of Saint Marina or Marinos is found in the hagiographies of the Syriac, Maronite, Coptic, Ethiopian, Greek and Latin Churches. Many biographies on this Saint were written in Syriac, Coptic, Arabic, Greek, Latin, Ethiopian, Armenian, German, French, and Spanish languages. From the considerable amount of manuscripts and writings, we can presume the veneration and honor that this Saint had once enjoyed in both the Eastern and Western world during the medieval era. Many of the Latin, Syriac, and Arabic manuscripts are to be found, among others, in the Bibliothèque Nationale in France; Bruxelles Bibliothèque Royale in Belgium; British Museum Library in London; Bibliothèque Ambrosienne in Milan; Saint Catherine Monastery in Sinaï; the Vatican Library in Rome; The Maronite Patriarchal Archive in Bkerke, Lebanon; the Bibliothèque des Missionnaires Maronites known as the Kraym, Jounieh, Lebanon; and the Bibliothéque Orientale De Beyrouth, Lebanon. Clugnet in his article Vie de Sainte Marine in the Revue de l’Orient Chrétien gives an extensive bibliography of the manuscripts pertaining to Marina and their whereabouts (Clugnet 1904: 588-594). The account of Marina’s life was known before the eleventh century. It was confirmed by writer Aba Al-Rayhan al-Bayrouni (+ 1049) in the eleventh century when speaking about the Syriac months in his book Al-Athar al Baqiyat ‘an al Qouroun al Khaliat (The Remained Remnants from the Passed Centuries): "On the third of October is the feast of the Monk Maria, who wore the cloth of man and became monk, who hid her femininity from the monks, then was accused of adultery with a woman. She did not reveal her femininity until her death which made known her situation and her innocence from adultery when they wanted to wash her [for burial]" (Al-Bustani 1983: 39-40). Marina’s legend has been an inspiration to several writers among whom we find Jacques de Voragine in his Légende Dorée; Charles Corm in Sainte Marina la Libanaise; Father Moubarak Thabet in Marinos: the Monk of the Monastery of Qannoubine (in Arabic); Father Michael Mouawad in The White Sin (in Arabic) and Patriarch Youssef Al-‘Akoury in his Ode for Saint Marina (in Arabic) written in 1641 and published by L. Clugnet in the Revue de l’Orient Chrétien in 1904. III. THE HAGIOGRAPHY OF MARINA THE MONK According the Maronite current Synaxarium, "Marina was born in Qlamoun North Lebanon. Her father was a pious man. Her mother died while Marina was very young. This has made her father renounce the world and leave for the Monastery of Qannoubine in the Holy Valley; accompanying him was his daughter, whom he dressed like a man. Both father and daughter entered into monkshood without revealing the identity of the daughter to the monks. As a monk she was known by the name Marinos. Although young, Marinos occupied himself with the practice of monastic virtues with utmost spirit and minuteness. He was silent and reticent with bowed head and eyes, making of his cowl a veil concealing the features of his face and eyes. One day he was sent to a neighboring town on a mission for the Monastery. He was obliged to spend the night at the house of a friend of the monks named Paphnotius. Paphnotius had a young girl who had fallen into adultery and was found pregnant. Upon finding out, her father was enraged and demanded the name of the perpetrator. His daughter told him that Marinos the Monk had raped her the night he spent in their house. Her father went straight to the Monastery and told the Superior, who was surprised for he knew that Marinos is a pious and pure man. The Superior called Marinos and scolded him, but Marinos said nothing to defend himself. Consequently, the Superior was very perplexed and considered Marinos’ silence to be an admission of guilt. He then sentenced Marinos to dismissal and to be thrown outside the Monastery. Marinos resigned himself to the will of God and stayed at the door of the Monastery praying and crying, living of the leftovers of the monks’ food. His father had long since died. When the daughter delivered, the grandfather brought the child, a boy, to the Monastery and threu him to Marinos saying: take and raise your son. Marinos took the boy and began raising him with what the monks used to bring to him of goat milk and of leftovers from their table. This situation lasted four years. Marinos carried the shame of this hideous accusation without any complaints. However, the Superior had compassion for him and let him enter the Monastery under very strict conditions. Marinos accepted while shedding the tears of repentance. Marinos persevered in his ascetic work until the hour of his death when the features of his face glowed with a heavenly light. He asked forgiveness from all and he forgave all those who sinned against him. He then gave up his spirit. The Superior then ordered that his body be prepared for burial outside the Monastery. It was a great moment of astonishment when the monks found that Marinos was a woman and not a man. The Superior and the monks fell on their knees before the pure cadaver, asking God and the soul of the holy saint forgiveness. As for the father of the sinful daughter, he was ashamed and came to make his statement before everyone. As for the daughter, she spent her life crying and repenting at the tomb of the saint. The sanctity of Marina spread all over Lebanon, people from all its regions came to the Monastery of Qannoubine to be blessed by her body. Her tomb became a source of cures and graces." (Daher 1996: 189-190) IV. DIVERSE VERSIONS OF HER BIOGRAPHY There are some additions or diversions of this rendition of Marina’s life. It is said that her parents names were Ibrahim and Baddoura at times, and Eugene and Theodora at others. It is also said that her father left her in the care of her caretaker and after a few years he returned to fetch her, at which time she insisted on going wherever he went. Furthermore, it is recounted that the superior, when punishing Marina for her deed, took her belt, which is to signify that she is no longer chaste, and no longer a member of the community. It is believed that upon receiving the child to raise, she cut a piece from her habit to swaddle him and that upon her retreat into the grotto to raise the child, she miraculously was able to nurse the infant from her own breasts. Another version states that she used to feed the child milk, donated by the shepherds who used the pastures in the vicinity of her grotto. Legend tells that when she died, the bells of the monastery rang on their own. An additional anecdote states that Marina lived at the door of the monastery crying, praying and begging to return to the monastery. Other renditions have the monks plead her case; and when the superior did not agree, they threatened to leave the monastery themselves. However, the story goes that the superior agreed but placed severe rules on Marina: fasting, adoration and vigil. When the superior was informed of her death, he ordered the monks to go to her cell, wash her, enshroud her, pray and bury her. It is when the monks began unclothing the body at the lavatory, that they uncovered her identity. Further additions state that, on her deathbed, Marina wrote a note to her brethren saying, "I am a woman and not a man. I embraced the monastic life with my father. I was falsely accused. I have raised this child with my care. I beg of you not to remove my habit my brothers" (Moubarak 1984: 4-5). When her identity was discovered, the superior knelt before Marina’s body, sobbed, and asked Marina to forgive him and to intercede in his favor before God. The monks prayed over Marina in the church while crying and lamenting. Suddenly, they heard a voice from heaven that told the superior "lift up your head from the ground; what you have done was not of your order or your will, but rather you have accomplished what the law commanded. Your sin is pardoned: don’t be sad anymore. As for how long she lived after the accusation, there are mainly two versions: one states that it was only 4 years and another states that it was 20some years. Tradition has it that Tourza, a village in north Lebanon about 29 km from Besharre, was the place of the sin that was laid on Marina. It is believed that because of the slanderer’s action, this village remained forever poor and was several times destroyed by earthquakes (Quaresimus: 1639: 800). The people of Tourza narrate that because of what happened to Marina, God have punished their village that was built on a mountain, by having it slip to the bottom of the hill where it is located today (Fiey 1978: 34). V. MARINA’S RELICS

In Paris, France, a small church dedicated to Saint Marina was located near Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral. This church may have been built between the tenth and the eleventh century.

In Lebanon today, there is no indication where Saint Marina’s relics are. Saint Marina, as we have seen, was venerated in many places and now is only revered in three – Lebanon, Cyprus, and Italy. VI. THE OFFICE OF SAINT MARINA AND THE ODE OF YOUSSEF AL-‘AKOURY A Maronite Office of Saint Marina in Syriac was first edited by Father Louis Cheikho. According to Mouawad, Cheikho did not provide information on the date nor the provenance of the Office. Mouawad states that, based on the colophon, the manuscript was copied by Father Boutros Makhlouf of Ghosta in c. 1720. The original author is unknown but that some attribute it to Patriarch Youssef Estphan (1766-1793) and others to Patriarch Estephan Douwayhi (1670-1704). (Mouawad 1998: 297) L. Clugnet published the manuscript in his book Vie et Office de Sainte Marine in 1905. The Office includes a version of Marina’s passion as well as other interesting details. (Mouawad 1998: 297) Patriarch Youssef Al-‘Akoury (1644-1648) composed an ode for the Saint in 1641 when he was still a Bishop. He wrote his ode in the colloquial Arabic of Lebanon. The ode is of 139 strophes, two verses. The Bishop identifies himself and dates the ode in the last twelve strophes (Clugnet 1904: 595-608). Clugnet published the manuscript in 1904. The following are extracts from the Maronite Office of Marina: Before the Epistle After the Gospel Before the Kiss of Peace Before the small Elevation VII. CONCLUSION This account on the life, legend, and relics of Saint Marina the Monk

tells us but little about her passion, suffering, and humiliation. The

Maronites remain to this day fascinated by this Saint. Among them, there

is almost a righteous anger against the injustice that was done to her.

To this day, her name is intertwined with that of the Monastery of Qannoubine

and her nearby grotto is a reminder of her chastity, obedience, asceticism,

humility, forgiveness, and sainthood.

Bibliography Al-Bustani, F. E. Marina al Lubnaniat Rahibat Qannoubine (The Lebanese Marina: Monk of Qannoubine) in Arabic, Beirut, 1983. Al-Bustani, K. Thalath Kiddissat min al Shark (Three Women Saints from the Orient), Al-Matba’a Al-Katholikiyat: Beirut, 1959. Bardswell, M. A Visit to Some of the Maronite Villages of Cyprus, Eastern Churches Quarterly, Vol. III, N° 5, 1939, pp. 304-308. Clugnet, L. Vie de Sainte Marine (Suite) (1), Revue de L’Orient Chrétien, Vol. 9 (1904), pp. 560-594) Daher, B. Al-Sinksar bi Hasab Taks al-Kanisah al-Intakiah al-Marouniyah (The Synaxarium According to the Maronite Church) in Arabic, Lebanon, 1974. Fiey, J. De Quelques Saints Vénérés au Liban, Proche Orient Chrétien, Tome XXVIII, 1987, pp. 18-43. Guidi, I. and E. Blochet. Vie de Sainte Marine (Suite) (1), Arabic Text, Revue de L’Orient Chrétien, Vol. 7 (1902), pp. 245-276. Lewis, A. S. Select Narratives of Holy Women from the Syro-Antiochene or Sinai Palimpsest, Studia Sinaitica, No X, London 1900, pp. 36-45. Mathon, G. Marine, Sainte. Catholicisme, T. 8, Letzouey et Ané, Paris, 1979, pp. 682-683. Moubarac, Y. Pentalogie Antiochienne, Domaine Maronite, Tome II, Volume 1, Beyrouth, Liban, 1984. Mouawad, R. Sainte Marina: Une Moniale dans la Vallée de la Qadisha, Actes du Colloque-Patrimoine Syriaque VI, Antelias, Lebanon, 1998, pp.271-285. Nau, F. Histoire de la Sainte Marine, Syriac Text, Revue de L’Orient Chrétien, Vol. 6 (1901), pp. 283-290. Sader, Y. Painted churches and Rock-Cut Chapels of Lebanon, Dar Sader: Beirut, 1997. Sauma, V. Sur les pas des Saints au Liban, FMA, Beyrouth, 1994. Sfeir, P. Les Ermites dans l’Église Maronite: Histoire et Spiritualité, Bibliothèque de l’Université Saint-Esprit, Lebanon, 1986. Tabet, M. Riwayat Marinos Raheb Deir Qannoubine (The Novel of Marinos the Monk of the Monastery of Qannoubine), Al-Mashreq, Beirut, 1956, pp. 79-128. |