SYRIAC CHRISTIANITY:

YESTERDAY, TODAY AND FOREVER

By Paul S. Russell, Associate priest at The Anglican Parish of Christ the King, Washington, D. C. and Lecturer in Theology at Mount St. Mary’s College, Emmitsburg, Maryland.

This paper was presented at the 37th Annual Convention of the National Apostolate of Maronites, Washington, D.C. USA, July 7th, 2000.

I. INTRODUCTION

It is a great pleasure for me to be here with you today and to have the opportunity to speak to you about a subject that is dear to my heart. It is a daunting thing to be asked to speak to you about your own tradition, but it may be that those of us who live our Christian lives outside of the Syriac tradition are able to recognize more clearly its great riches and peculiar benefits. At least, that will be my task today: to try to tell you many things you already know, and perhaps a few that you do not, and then to try to suggest what these things can show us about what Syriac Christians have done for the universal Church and what they can do for it in the future.

I have decided to divide my remarks into three parts to demonstrate the three parts of the title that Fr. Dominic Ashkar (Pastor of Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Church in Washington, D.C.) helped me devise: where the Syriac Church has been, where is it now (especially its Maronite component), and where it might go in the future. I will try to describe to you some things about the spread of Syriac Christianity and its influence in India, Central Asia, China and, finally, in England. Once we have examined that spread through space, we will turn to take a look at a piece of writing that can serve as an example of some of the Syriac tradition’s characteristic qualities. Those two elements: the geographical spread of its influence and the quality of its Theology will, I hope, give us some idea of what we are referring to when we talk about what Syriac Christianity can do with its tradition as it looks forward to the future.

We will begin in the past, as our faith did and as Christians always do when they try to understand themselves. That is why The Letter to the Hebrews 13:8 can speak of Jesus Christ “yesterday, today and forever” and why we speak of Syriac Christianity in the same way. We have a history we can trace and tracing it is how we come to know ourselves. So, we begin at the beginning of the Church’s spread: at Pentecost.

II. SYRIAC CHRISTIANITY: YESTERDAY

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. And suddenly there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other

tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance. And there were dwelling at Jerusalem Jews, devout men, out of every nation under heaven. Now when this was noised abroad, the multitude came together, and were confounded, because that every man heard them speak in his own language. And they were all amazed and marveled, saying one to another, Behold, are not all these which speak Galilaeans? And now hear we every man in our own tongue, wherein we were born? Parthians, and Medes, and Elamites, and the dwellers in Mesopotamia, and in Judaea, and Cappadocia, in Pontus, and Asia, Phrygia, and Pamphylia, in Egypt, and in the parts of Libya about Cyrene, and strangers of Rome, Jews and proselytes, Cretes and Arabians, we do hear them speak in our tongues the wonderful works of God. (Acts 2: 1-11)

This scene of the Pentecost, from the beginning of the second chapter of The Acts of the Apostles, reminds us of two important things:

A: From the very first, the Church spread from Jerusalem to the East, since we can see that many of those converted on that first day of Pentecost were from the East: “Parthians [Parthia was the empire located just East of the Roman Empire that included roughly what we now call Syria, Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan], Medes [Medes might be Persians, or people from Asia Minor]...dwellers in Mesopotamia...Arabians [these two we all can recognize]”, and

B: The new faith of the Church was carried first to the world by Jewish believers in their own languages. Toward the East, that language was predominantly Aramaic. What we call “Syriac” is a western form of Aramaic usually written in a different alphabet than the Hebrew and Aramaic Old Testament.

As much of the very early history of the Church as we can discover follows this pattern quite closely: traveling Christians: missionaries, but also, more usually, Christians who were traveling anyway on business, carried the faith with them as they moved to the East and South. We can trace them East to Edessa, which would become one of the great centers of the Syriac speaking Church, to India, to Persia, to central Asia and even on to China, where we have physical evidence to record the arrival of Christians there no later than 635 AD.

We all know something of the spread of the Church to the West, because that is where we live. We know of the missions to the Romans and the Goths, to the Slavs and the Norse Vikings, to the Irish (this is very fashionable now) and even to the American Indians. I would like to tell you just a few things about the Church’s spread to the East, to offer you just a few drops from the great ocean of the history of the life of the Syriac Church, and to try to demonstrate to you a few points that I think are important for understanding the genius of your tradition. I will try to convince you of the truth of three ideas:

A) The Syriac Church is a unifying tradition.

B) The Syriac Church offers culture and learning wherever it goes.

C) The Syriac Church has a creative and intelligent theological voice.

If we imagine the map of the world spread out in front of us, we would see the Latin Church in the West (to the left), the Greek Church in the middle, and the

Syriac Church to the East (on the right). Over the course of time, each of these traditions worked hard to spread the Gospel to those with whom it had contact. The Latins moved through Western Europe and North Africa, the Greeks moved northwards through Eastern Europe and southwards into Egypt and Ethiopia, and the Syriac Christians spread through the whole of the great landmass of Asia. As we look back at this process, we can see that, while the use of Latin spread with the western Church and served to bind it together as a group, that unity became more and more one that excluded their brothers to the East so that, by the time of the ecumenical councils of the Fifth Century (Ephesus II, 449 AD), we have stories of the legates from the West being unable to join in the discussions or understand the business of the council because they no longer could talk to their brother Christians. Latin Christianity and Greek Christianity had grown apart. (I am hardly hostile to the western Church and its tradition. I speak as a person whose family background is a mixture of Scottish, English, Welsh and French. All of these are groups that were evangelized by the Latins at the very edge of their world. For my ancestors in the western reaches of the Latin Church, there was a great benefit in being offered Christianity in a form that could be shared with people all the way to what is now Yugoslavia, but their Christian brothers to the East were cut off from them by barriers of language more than of distance.)

The Greeks were always more open to allowing groups to make their own way forward in the faith than the Latins were (as the Orthodox traditions of worship that continue to be active in many languages attest), but they, too, tended to offer their converts what they knew, which was the tradition of the Greek East.

When we turn to look at the tradition of Syriac Christianity, I think we see something different.

A. The Syriac Church as a Unifying Force.

I would like to share with you some pictures produced by the Syriac Church that will illustrate some of this unifying quality in its tradition. I think they help make my point more convincing.1

|

1) This comes from a Gospel Book, ca. 1054 AD, in the library of the Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate in Damascus. Notice that the scroll Our Lady holds has writing in both Greek and Syriac on it. The Syriac says: “My soul doth magnify the Lord and my spirit doth rejoice in God my Savior. For He hath regarded the lowliness of His handmaiden.” I think that the Greek comes first because the icon-writer knew that the New Testament original was in Greek. The writing by Mary’s head is also bilingual. The book this is found in is a book of Gospels in Syriac. Are these people cutting themselves off from their fellow Christians on the basis of language? |

2) This icon of the Resurrection, from 1219-20 AD, is found in the Vatican Library. Notice how it contains elements that reflect both the current events in the lives of the Syriac Christians (the soldiers look Asian or Turkish as Muslim soldiers of the time increasingly were) and the customs of the greater Church. (The figure of Jesus tries to be in tune with the standard pattern of the western Christians--the Greeks.) The Syriac Christian artist is looking both East and West.

2) This icon of the Resurrection, from 1219-20 AD, is found in the Vatican Library. Notice how it contains elements that reflect both the current events in the lives of the Syriac Christians (the soldiers look Asian or Turkish as Muslim soldiers of the time increasingly were) and the customs of the greater Church. (The figure of Jesus tries to be in tune with the standard pattern of the western Christians--the Greeks.) The Syriac Christian artist is looking both East and West.

3) This is from the same manuscript as the last and shows two scenes of Christ with the paralytic. He cured, the one who had been lowered through a hole in the roof by his friends. “Take up your bed and walk.” Notice how the disciples are dressed some as Romans (upper right) and some in a more eastern style. The artist has both good historical knowledge and a sense that the life of Christ was lived in the Middle East. Western books might have the figures in western dress of their own time: Pilate in Medieval armor and Herod dressed like an Italian prince.

3) This is from the same manuscript as the last and shows two scenes of Christ with the paralytic. He cured, the one who had been lowered through a hole in the roof by his friends. “Take up your bed and walk.” Notice how the disciples are dressed some as Romans (upper right) and some in a more eastern style. The artist has both good historical knowledge and a sense that the life of Christ was lived in the Middle East. Western books might have the figures in western dress of their own time: Pilate in Medieval armor and Herod dressed like an Italian prince.

4) These scenes are found on the wall of the Monastery of Moses the Ethiopian in Nebk, Syria. The top scene is of the Virgin, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob saving souls at the Last Judgment; the bottom shows St. Peter opening the gates of Heaven. Notice how western St. Peter looks (being associated in the artist’s mind with Rome, of course, and standing for the Western Church), while the saints entering the gates have more in common with the inhabitants of the monastery. The artist imagines both East and West present in the Kingdom after Judgment.

5) This little figure is St. Ephraem, the great hymn writer, who lived in Nisibis for most of his life and died in Edessa in 373 AD. This is in the library of the Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate in Damascus and was painted in the 12th century. Notice how this authentically Syriac Christian figure is shown in an authentically Middle Eastern way.

5) This little figure is St. Ephraem, the great hymn writer, who lived in Nisibis for most of his life and died in Edessa in 373 AD. This is in the library of the Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate in Damascus and was painted in the 12th century. Notice how this authentically Syriac Christian figure is shown in an authentically Middle Eastern way.

These five pictures have shown us that the Syriac Christian artists had a clear idea of the breadth and variety of the whole of the Church and tried both to represent that variety and to help the different parts of the Church remain united in their art (and in the minds and hearts of those who looked at their works).

Let us turn now for a moment to some physical monuments and remains of the spread of Syriac Christianity.

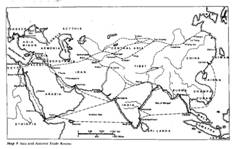

6) This is a map of Asia with routes of travel marked on it. You can see the various paths by which people customarily journeyed. It is precisely along these lines that we can trace the spread of the Syriac Church.

6) This is a map of Asia with routes of travel marked on it. You can see the various paths by which people customarily journeyed. It is precisely along these lines that we can trace the spread of the Syriac Church.

All the traditions we have about the coming of the Gospel to India agree that it came from or through Mesopotamia to get there. Whether it was brought by the Apostle Thomas himself (and there is certainly no reason why it could not have been), or whether his original evangelism was extended by other brave souls whose names we do not know, it is clear that Syrian Aramaic Christianity is what was offered to converts in North and South India.

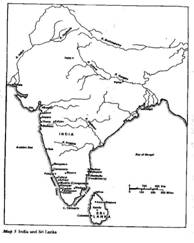

7) This map shows the locations of known early Christian sites in India and Sri Lanka. You can see that they are grouped in just the areas one would expect if they were created by people moving along the lines we have suggested. One of the points to remember in this is how much the ordinary lay people were involved in the spread of their faith. There were many heroic clerical missionaries, of course, but most people seem to have come to the Church through contact with the ordinary faithful. (That lesson is one we should all keep in mind when we think of the present need to spread Christianity to those around us.)

7) This map shows the locations of known early Christian sites in India and Sri Lanka. You can see that they are grouped in just the areas one would expect if they were created by people moving along the lines we have suggested. One of the points to remember in this is how much the ordinary lay people were involved in the spread of their faith. There were many heroic clerical missionaries, of course, but most people seem to have come to the Church through contact with the ordinary faithful. (That lesson is one we should all keep in mind when we think of the present need to spread Christianity to those around us.)

How did they present it to their listeners? The evidence of these crosses seems to me to argue that they couched it in terms that would meet the converts on their own level (as the native language inscriptions shows) while guarding that part of their message that would continue to connect their followers with their Christian brothers and sisters back in Mesopotamia, Persia and the Holy Land. Because Asia is one great landmass, Syriac Christians lived in a world where many different types of people had easy contact with one another (which was often not the case for Christians in the West), they seem to have understood that to keep the lines of that contact open would allow for a broader and more vibrant Church than if each local area had to fend for itself. Examples of this are many, but I will only mention that it was the custom for Bishops in the Indian Church to travel to Persia to be consecrated (not an easy feat, even in the 21st century!)2 and that this seems to have been the regular practice for most of the life of that Church. It is also known that the Syriac Christians living all the way to the East in China communicated regularly with their ecclesiastical superiors in Persia (a journey often taking more than a year--each way!) In fact, in the 14th century, the Church of the East had for its Catholicos (Patriarch) a monk who was born north of Peking in what is now China, and that Patriarch sent a legate from Baghdad (who was also from China) to the Christians of Western Europe. This legate, Rabban Sauma, visited Constantinople, Italy, and France, and had audiences with the kings of France and England and with Pope Nicolas IV. (He was received with respect and honor in the Vatican and allowed to celebrate Mass at the altar in Saint Peter’s, a Mass which the Pope attended.)3

Now that we have had a brief look at the manner of the Syriac Church’s spread in India, which produced a Church that continues to the present day. Let me show you a few things from the Syriac Christians of Central Asia:

B. Effects on Culture

The Syriac Church was affecting many groups of people it met. We see evidences in Manichaean and Soghdian texts discovered in what is now known as Uzbekistan.

The fragments of a psalm text in Syriac from the 9th to the 10th century found in Uzbekistan and a Manichaean text from a Manichaean temple in Kocho (8th-9th century) in which the figures are Chinese in appearance, with traditional high white hats worn by Manichaean clergy, but their language is a script taken from Syriac. Mani was the first in a long line of people who have claimed to be Jesus Christ returned and the connection to Christianity that forges for the Manichees seems to have allowed them to piggyback on Christianity through much of the area the church had managed to penetrate. Saint Augustine was a Manichee for more than a decade, meeting with the religion in North Africa, and these Manichees were all the way on the border of the Chinese Empire, still clinging to Syriac writing from an idea that it is culturally sophisticated. There is Manichaean prayer written in the Uighur language (a Turkic tongue) clearly shows that the alphabet is Syriac. This indicates that the Manichees using the Syriac alphabet were not only transplanted Mesopotamian people using their own national script, but also people native to Central Asia.

There is a Soghdian text, also with Syriac script. Soghdian was the language of an important merchant people living along the Central Asian Silk Road. Bukhara and Samarkand were in their sphere of influence before the arrival of Islam. This is also in the area we now call Uzbekistan. The Soghdian people flourished in the period following 600 A.D. Soghdian was the preserver of a lot of Christian writings in this area.

The following photos and descriptions will give you an idea about the magnitude of the influence that the Syriac Church have had on those it has converted and on those it has not. Remember that this influence was being felt in a world where many strong cultures were active. These examples should not be thought of as being influences that Syriac Christianity wielded because it had no competitors. The effects I will try to show you were felt against a backdrop of vibrant, attractive options.

1) This photo shows the wide variety of embroidered crosses produced among the Asian Syriac Christians of what we would call the early Middle Ages. These crosses and others like them are always common finds in all parts of globe where the Church has spread because of the use of so many kinds of linens in worship.

1) This photo shows the wide variety of embroidered crosses produced among the Asian Syriac Christians of what we would call the early Middle Ages. These crosses and others like them are always common finds in all parts of globe where the Church has spread because of the use of so many kinds of linens in worship.

2) This photo shows the famous monument found at His-an-fu in 1625. His-an-fu was the ancient and original capital of the Chinese Empire. You may remember the many thousand clay soldiers discovered a few years ago in China and often shown in pictures in the West. (National Geographic did an article on them a while ago.) They were also found in His-an. This monument is of particular interest for the history of the spread of Syriac Christianity. The stele was unveiled on February 4, 781 and speaks of the arrival of Christianity in China as having happened in the year 635 AD. This marks the “official” arrival of Christianity in China. There may well have been Christians in China before that time.4

2) This photo shows the famous monument found at His-an-fu in 1625. His-an-fu was the ancient and original capital of the Chinese Empire. You may remember the many thousand clay soldiers discovered a few years ago in China and often shown in pictures in the West. (National Geographic did an article on them a while ago.) They were also found in His-an. This monument is of particular interest for the history of the spread of Syriac Christianity. The stele was unveiled on February 4, 781 and speaks of the arrival of Christianity in China as having happened in the year 635 AD. This marks the “official” arrival of Christianity in China. There may well have been Christians in China before that time.4

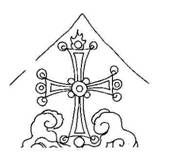

To begin with, the Chinese text of the monument refers to Christianity as “the Syrian Luminous Religion” (its official legal name in the empire), which makes it clear where the Chinese government thought the Gospel was coming from. The text also refers to God as “the Lord, Alaha”, which is clearly Syriac. Notice what the decoration of the Cross atop the stone shows us.

3) The Cross rests on the cloud of Islam and on top of the lotus of Buddhism. The Church was competing in China against other non-Chinese religions and claimed to be winning. (The Syriac Christians in China were not timid.)

3) The Cross rests on the cloud of Islam and on top of the lotus of Buddhism. The Church was competing in China against other non-Chinese religions and claimed to be winning. (The Syriac Christians in China were not timid.)

At the bottom of the stone are carved the names of the clergy in Syriac script and then in Chinese equivalents. Some of the list includes Yohannan, Isaac, Joel, Michael, George, Ephraim, David, Moses, Abdisho, Simeon, Aaron, Peter, Job, Luke, Matthew, Ishodad, Constantine (!), Sargis, Zechariah, Koriakos, Emmanuel, Solomon and Gabriel. We have no way of knowing what ethnic background these people came from (they might have been Middle Eastern, Chinese, or anything in between), but it seems clear where their Christianity was coming from. Even 2,000 miles from the land of spoken Syriac, the Church was maintaining its linguistic ties with its brothers back home.

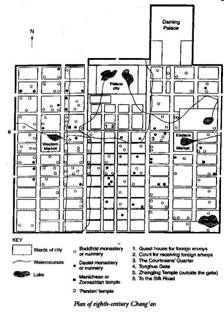

4) Here is a map of Hsi-an in the 700s, the time of the monument.5 A place is marked “Persian temple” on the map, which I take to be a church. Zoroastrian sites are listed separately, and no other religion seems likely. The Syriac Christians in Hsi-an corresponded with their fellows in Persia for support and news about the Church, so having the Chinese call them “Persian” or “Syrian” makes equal sense. Both places were as far away as the moon for the Chinese of that time, anyway.

4) Here is a map of Hsi-an in the 700s, the time of the monument.5 A place is marked “Persian temple” on the map, which I take to be a church. Zoroastrian sites are listed separately, and no other religion seems likely. The Syriac Christians in Hsi-an corresponded with their fellows in Persia for support and news about the Church, so having the Chinese call them “Persian” or “Syrian” makes equal sense. Both places were as far away as the moon for the Chinese of that time, anyway.

The capital of China at that time had more than 1,000,000 inhabitants, according to the latest guesses. The lay out is easy to understand: trade arrived from the West (left) and East (right). The Christian church, as one would expect, was near the gate through which the Gospel arrived along the Silk Route. I think this fact, which places the Christians among the traveling merchants and those who had contact with them, shows that the Syriac Christians at the other end of the world in the 700s were spreading the Gospel through personal witness and contact, just as those witnesses of Pentecost did 700 years before them. People who wanted either exotic items from the West or instruction in the Christian faith would have known where in Hsi-an those things could be found.

What have we seen of the Church’s influence, then? The Church was passing along its own writings in its language of worship and those around it were spurred to write down their languages (which they had not done before) in the script that the Church brought with it. We have seen, also, that the Church was still associated in the minds of those around it with the Syriac Christians who brought it with them and that it still (even in Chinese) spoke of God with the Syriac word “Alaha”. The Chinese name for the Church, “the Syrian Luminous Religion”, shows us that this connection was strong, and the location of the church building in the city supports that connection.

Before we leave this section of our discussion, I would like to reiterate one point about the role of the Syriac Church in this area: it seems clear to me that the Church was serving as a unifying force among the various Silk Road peoples who made up its membership and that this influence could even spread beyond its boundaries and include those who were not converted to the Faith. Rather than dividing people, Syriac Christianity seems to have served to give them things in common across racial and linguistic boundaries.

Before we leave off considering influences, I have one more thing I would like to tell you about with regard to the Syriac Church’s influence in the past. For this, we must focus our gaze all the way at the other end of the world from the Chinese Empire, on England at the time of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.6 It is a mistake to think of Syriac Christianity’s influence as confined to the Holy Land and points to the East; it has been of importance at various times in my own national Church, the Anglican Church, as well.

There were Christians in Britain during the Roman Empire. There seem to have been bishops in London and York, at least. This Church was poor and seems to have been small. It seems to have dwindled to the point that, by the time of Pope Gregory the Great (590-604), the island seemed, to outsiders at least, in need of being reconverted. (We seem to be fast approaching that situation again, I fear.) After Saint Gregory had sent Saint Augustine of Canterbury to Kent, where he became the first Archbishop of Canterbury, the Church in England revived, but was still in an uncertain state.

In 664, with turmoil setting in, Pope Vitalian thought it best to send another archbishop from Rome to settle things down. He tried to send a monk named Hadrian (“an African by race”, Bede called him) but instead settled on an elderly (66 years old) monk from Tarsus (Saint Paul’s home) called Theodore. (Hadrian came as one of his companions, so the group was very international in its make-up.) The new archbishop who arrived in the rugged western island was a scholar from the Middle East, which must have made him a fish out of water in the England of the 660s! Theodore, to everyone’s surprise, lasted more than 22 years as archbishop!

Scholars think that Theodore knew Syriac. He is likely to have begun his theological study in Antioch, where Greek and Syriac were in common use at that time. He may even have been to Edessa.

Theodore set up a school in his monastery in Canterbury and manuscripts of notes on Scripture survive that were written by his pupils. Often, the particular comments are clearly labeled as coming from Theodore or Hadrian. At a number of points, scholars have identified comments as having been drawn from the works of Saint Ephraem the Syrian. One of these comments even mentions Saint Ephraem by name, which shows that the English students in the school (where the language of instruction was Old English) knew that they were being taught the doctrine of the great Syriac Doctor.

Some of the passages from Syriac writers that are reflected in the commentary notes the students produced are not known to have existed in Greek or Latin translations. This would mean that, unless translations were made and all trace of them is now lost, we have evidence of direct influence of Syriac Christianity on what was taught to Anglo-Saxon students in Canterbury and then, presumably, through preaching and teaching, to their laity. Some scholars think that Theodore brought Syriac books with him for his own use when he arrived in England. These would most likely have been works of Saint Ephraem.

The evidence seems to support the conclusion that Theodore of Tarsus, and those who accompanied him, brought with them, either in their heads or written in books (or both) some knowledge of the teaching of writers from the Syriac Christian tradition, with Saint Ephraem prominent among them. This means that at both ends of this process: at Antioch and elsewhere in the Middle East, and in Canterbury in the Kingdom of Kent, the Syriac tradition was attractive enough to these Christians to be noticed and studied and passed along. Because this all happened early in the history of the Church, the walls of language and politics had not yet blocked travel and contact between Syriac and Greek, Greek and Latin and Latin and Anglo-Saxon. So, the teaching of the East was able to make its way all the way to the West, past the Pillars of Hercules and out to the isles in the Western Sea. By the year 700 AD, Syriac Christianity had spread its influence to China, India and England: all the bounds of the world as they were then known, except only the North, whose Slavs and Scandinavians would remain pagan for another 300 years.

Before we leave England, though, I would like to point out that Syriac Christianity has not only influenced us in the distant past. When Syriac and Syriac writers became known again in England, after the Reformation, its influence began to be felt again. To my knowledge, more attention has been paid to tracing this in the 1800s than to finding it earlier,7 but the pattern is clear: when English Christians have had access and exposure to Syriac Christian works, these writings have had a profound effect on us. Our ideas of the mystery of God and the sacramental nature of the world have been deepened and enriched by being exposed to your tradition. Recently, we have not felt this effect as much as at other times, but I hope (and my own work is an attempt to help spur this along) that a renewal of interest and benefit is in the beginning stages now.

C. The Syriac Church’s Theological Voice

We will now leave off discussing the Syriac Church’s role in spreading culture and learning and turn to a quick look at its theological voice. What can I show you in a few minutes about a topic that a lifetime cannot exhaust? We might begin by reminding ourselves that Syriac Christianity has never made an idol of its Theology. St Ephraem, the greatest of the Syriac Fathers says in Hymns on Faith 4.13:8

This is suitable for the mouth:

That it might praise and be still and,

If it should be asked to run on,

It would entirely resist, in silence.

Then it will be able to comprehend,

Unless it runs on in order to comprehend.

Stillness is able to comprehend

More than the insolent [person] who runs on.

Saint Ephraem means that when we are speaking about God we had better be ready to realize our own shortcomings and keep silent so that we do not fall into the sin of presumption by boldly attempting to describe Him Who is beyond us in every way. Still, we are religious creatures and living our religion requires some speaking about God, and we must certainly speak to teach our religion to our children. (Saint Ephraem certainly knew all this. He was, himself, a great talker about God, after all.) So, I would like to show you just one element in Syriac Christianity that will serve to illustrate its sensitivity and creative power. I would like to show you a taste of the things it has to say about Our Lady, the Blessed Mother, the Virgin Mary, and the Theotokos.

These passages I will show you are taken from a Dialogue Hymn that shows the Holy Virgin in conversation with the angel Gabriel on the occasion of the Annunciation. I know that these hymns are in use in your liturgies and that you know much more about them than I do (because Theology is best learned in worship and prayer. This is the basic insight Fr. Dominic Ashkar makes use of in his book Transfiguration Catechesis, and the universal Christian tradition would enthusiastically agree.)9 Still, I would like to tell you how these lines appear to me, as I stand outside your Church, looking in.10

The first stanza of the hymn reads:

O Power of the Father who came down and dwelt,

Compelled by His love, in a virgin’s womb,

Grant me utterance that I may speak

Of this great deed of Yours which cannot be grasped.

The first thing I notice is that the hymn is theologically and religiously serious. It makes the point, through the voice of the narrator, that it is only with the grace of God that we can hope to speak of the Incarnation of God the Son, without which we can have no understanding of the divine nature and without which our ability to approach God would be much more restricted.

As we read this hymn, we discover that when Mary first hears the words of the angel, her instinct is to push away his message because it seems too good to be true:

Mary 18:

I am afraid, sir, to accept you,

For when Eve, my mother, accepted

The serpent who spoke as a friend

From her former glory was she snatched away.

This is not only psychologically astute on the part of the writer of the hymn, for it seems to me that a smart girl should have been cautious toward strangers who appear to offer her something beyond what seems reasonable, (I hope my daughters are learning similar caution, for it will serve them well in life), but this attitude shows the Holy Virgin as a careful and intelligent religious thinker. She knows that the relations between God and human beings have a history and that that history is meant to guide us in our dealings with the Lord in our own lives. Mary has learned the lesson of the Fall from the Garden of Eden and does not mean to make that mistake again. She is shown to us clearly as Eve’s superior: a woman who can start our race back on its road to Heaven, instead of pushing us farther into the troubles we have already made for ourselves.

The hymn continues, a few stanzas later (stanzas 21-22)

Angel 21:

The Father gave me this meeting here

To bring you the salutation and to announce to you

That from your womb His Son will shine forth,

So do not answer back in contrariness.

Mary 22:

This meeting with you and your presence here is all very fine,

If only the natural order did not stir me

To have doubts at your arrival

About how in a virgin there can be fruit.

The angel’s temper is beginning to fray (angels are probably not used to back-talk), but Mary’s concerns are not frivolous. More than that, Mary’s doubt is not a sign of a lack of faith, but rather a sign of the strength of her faith. She will not acquiesce automatically to something that does not fit into her religious sense of what God is and how He works. She does not accept as true something that violates the natural order of God’s creation unless she has some reason to think that God is choosing to over-ride His general arrangement of things in this particular instance. This caution is a sign of intelligent reverence, not of confusion or of a desire to cause difficulties. So, they continue, a bit further on:

Angel 33:

He will come to you, have no fear,

He will reside in your womb, ask not how.

O woman full of blessings, sing praise

To Him who was pleased to be seen in you.

Mary 34:

Sir, no man has ever known me

Nor any ever slept with me;

How can this be, what you have said

For without such union there will be no son?

Angel 35:

From the Father was I sent

To bring you this message, that His love has compelled Him

That in your womb His Son should reside,

And over you shall the Holy Spirit reside.

Mary 36:

In that case, o angel, I will not answer back:

If the Holy Spirit shall come to me,

I am his maidservant, and he has authority;

Let it be to me, Lord, in accordance with Your word.

Once Mary has seen that this promised event is one that connects with and fulfills her faith in God (as the coming of the Holy Spirit would do), she is eager and willing to do her part. You notice that stanza number 36 echoes the words of Mary in Luke 1:38: “Behold the handmaid of the Lord. Be it unto me according to Thy word.” This hymn is both creative and fully scriptural, at one and the same time. Before we leave this hymn, let me just show you that the characteristic Syriac religious reluctance to speak about the Divine Nature is not lost as a result of the Incarnation:

Mary 46:

I should like, sir, to put this question to you:

explain to me the ways of my son

who resides within me without my being aware,

what should I do for him so that he is not held in contempt?

Angel 47:

Cry out ‘Holy, holy, holy’

Just as our heavenly legions do, adding nothing else,

for we have nothing besides this ‘Holy’,

this is all we utter concerning your Son.

This is just the reaction that Saint Ephraem advocated in that first passage we looked at: “This is suitable for the mouth: that it might praise and be still....” The angel wants Mary to praise the infant Jesus and then to hold her tongue. The Syriac tradition consistently holds to the idea that appropriate speech is required of us, but that more than that is not permitted.

What do we see of Syriac Christianity in these few lines? I see at least two things:

1) This is a serious work of theological writing. It is careful about what it says and keeps to the boundaries it sets itself.

2) This hymn has a clear picture of Our Lady in mind: she is not a “plaster saint”, who looks good but has no personality, she is a human individual with her own ideas and concerns. She is a model of religious devotion for her willingness to do the will of God, but she is a model of theological devotion because her belief and obedience are not blind and unreasoning, but intelligent and thoughtful. She is not the model of those who would make of the Church a mindless cult where you have to leave your mind and ideas at the door in order to gain admittance; she is the model of a Church that will demand of its members the highest degree of intelligence and maturity. I think it is these qualities that have produced the glories of the Syriac tradition and are its hope for the present and future.

III. SYRIAC CHRISTIANITY TODAY

That brings us to “today”. Now that we have examined a few ways in which the Syriac Christian tradition has spread its influence in the past, and have said something about its characteristic theological vision, what can we say about the place of Syriac Christianity and especially of the Maronite Church in the world today?

The Syriac tradition has riches in its possession that no other branch of the Church possesses, but what good is it to have a lighted candle if you just put it under a bushel basket so no one can see its light?11 We are called to “let [our] light so shine before men, that they may see [our] good works, and glorify [our] Father which is in Heaven”. How is the Maronite Church to do that? We must think for a moment about what you are and where you are located in the Church and in the world.

The Maronite Church is unique in that it is an entire Syriac Church that is in full contact and communion with the Church in the West. The fragmentation of Syriac Christians has a long and tragic history and continues to be a source of pain and a cause of wasted energies among many Syriac Christian groups in our own day. Maronite Christians, though they have a long and noble history of suffering for their faith, have escaped the family quarrels of other Syriac groups, which is not a small blessing. As a part of the Roman Catholic Church (which is really more a family of churches than one single body), the Maronite Church enters fully into the life of the Church throughout the world and has access to Christians of all nations and backgrounds. There are Maronites found in their native land of Lebanon, in Europe and in the New World. Maronites study in universities and seminaries with Catholics (and non-Catholics) who will carry the Gospel into every corner of the globe. (My first teacher of Syriac was a Maronite priest, Father Joseph Amar, who now teaches at Notre Dame in Indiana.) You Maronites are organized as a church and as a people, which greatly increases your ability to muster your resources to achieve the goals that you set yourselves. If you set yourselves the goal of being the western world’s window to the riches of the Syriac Christian tradition, I think that you can do it, both because of your unity and the strength it affords you and because of your living among the Christians of the West. I must warn you, though; the West does not know the riches you have to offer them.

Let me tell you a story that will show you how little those around you know about you. During the last week of May this year, I attended, as I do three years out of four, the meeting of the North American Patristic Society at Loyola University of Chicago. The president of that organization this year was an Eastern Orthodox laywoman named Susan Ashbrook Harvey, a very good scholar, who teaches at Brown University in Rhode Island. Because she is a specialist in the Syriac tradition, she used her presidential address to display to that group some of the wealth of your tradition. (She made use of several dialogue poems about Mary to show how Syriac Christians have been astute enough to realize that one of the central messages of the gospels about the Incarnation is that they tell the story of real people making real choices to obey and further the work of God in the world. The disciples were not machines, and Mary was not a serene statue who never knew a moment’s worry.) Except for the few of us who work in this tradition, no one in that lecture hall seemed to be at all aware of the fact that these writings even existed and seemed to have no idea of what they were missing. I knew that the Syriac Church was under-appreciated, but I had no idea of the extent of the ignorance of the West before then. This was, after all, a collection of most of the professional scholars of early Christianity living in North America. (That experience moved me to choose to read you that dialogue poem and helped direct my remarks today.) I am sorry to have to report to you that, as far as I can tell, both you and I have much work ahead of us if we hope to make the Christians around us aware of the beauties of your tradition.

As far as “Today” is concerned, then, I must say that the Maronite Church is in an enviable position to offer its riches to the world, but that the world seems not even to be aware that it is missing anything. You are beginning the task of offering your tradition to your neighbors at absolute zero.

IV. SYRIAC CHRISTIANITY FOREVER

What, then, can (and should) the Maronite Church do to live out its calling in the world? The first thing you must do is to be yourselves. Just as a child can have no sense of itself if it does not know its name and family, so can a Church not know itself if it does not continue to be in touch with its history. At home, at the supper table, my wife and I spend a few minutes every once in a while telling stories about our families so that our children will know where they come from:

Why did we come to America?

Where did our families live before?

What did our ancestors do for their livings?

How did the two of us meet?

Why are they named what they are? (My son is named Gregory (for the Theologian) Ephraem Athanasius -- a theology lesson in itself, as I intended it to be.)

What are Anglicans and how are they different from anyone else?

Why do we pray the way we do?

Why do our Jewish friends not pray as we do?

Why do our Indian friends have statues of blue elephants in their house with candles lit before them? (America is a country like the world of the early Church.)

Maronites must be careful to tell their children all these things. You must take your children to Mass and see that they pray the liturgy of their fathers and mothers enough so that it comes naturally to their lips (and their hearts). You must read the works of the Syriac tradition when you read devotional works. (No one needs to be a scholar to be a Christian. Some of the greatest Christians never learned to read, but reading is a great blessing for a Christian and one can read much of the Syriac tradition in English now and more is available every year. Look, for example, at the list of books in the bibliography at the end of this article. If you read Syriac works, you will feed your faith and your knowledge of yourself at the same time.) If you can keep yourself and your tradition in your minds, it will be on your tongues and your children will know it well enough to want to know it better when they are older. We cannot make our children be Christians (I tell myself), but we can make them people who are ready to receive God’s grace to be made into Christians. We are preparing the soil and planting the seeds, but only God can make things grow. It is the same way with teaching the tradition.

Once the tradition is a part of their lives, they can be the means by which those around them (and I hope that my children will be among these people) can be exposed to the riches of the Syriac Church.

Now, before I close, let me tell you that the Maronite Church has already, in the past, performed the role of being the voice and presence in the West of the Syriac Christian tradition.

Some of you may know that one of the crown jewels in the Vatican Library’s incomparable collection of books and manuscripts is its collection of Syriac Christian works. How did these treasures find their way to the West, where they have been safe from destruction during the tragic disasters suffered by Christians in the Middle East during the Twentieth Century? Westerners did not value them and collect them; they were brought by Maronites.

Three members of the same family, the Assemani (or Al-Samani) family, served as librarians, professors, editors, cataloguers and witnesses to the treasures of the Syriac Church. Joseph Simon Assemani (1687-1768), born in Tripoli and educated at the Maronite College in Rome, made two long visits as a papal emissary to the Near East in 1717 and 1735, during which he collected large numbers of manuscripts and ancient coins for the Vatican collection. He became titular archbishop of Tyre and Vatican librarian, published an important collection (1719-1728) called Bibliotheca Orientalis Clementino-Vaticana (4 vols.) that began the modern period of publishing Syriac works.

His nephew, Stephen Evodius Assemani (1709 ca-1782), succeeded him as Vatican librarian and also published a catalogue of Oriental manuscripts in the Roman collections, which made it possible (and still makes it possible) for western scholars to locate works in the Church’s possession (as well as making them aware of the riches available). He was also one of those responsible for the great “Roman Edition” of the works of Saint Ephraem the Syrian (1732-1746), which is still a mine of information and a source of great enjoyment for many of us who work in the area of the Syriac Tradition.

Simon Assemani (1752-1821), Joseph’s grandnephew, was also born in Tripoli and educated at Rome. He returned to the Middle East to serve as a missionary and was later appointed Professor of Oriental Languages at the University of Padua in 1785. He published an important study of ancient coins and also investigated the culture and literature of the Arabs in the period before the rise of Islam. (I think that interest must have come from his time as a missionary, trying to think of how to bridge the gap between Christian and non-Christian in the Arab world.)

The work of all these men is still in use. I have seen their books being used in the library at Catholic University. In the minds of scholars, their names are linked forever with that of the Maronite Church and the Syriac Christian tradition. I am always conscious of them and their work as I struggle to learn more about the tradition they served so well. But scholarly work is not enough. Churches need people who are living and personal witnesses of what they have to offer, if their message is to be heard. Once the scholars have done their part, the people must make use of the resources that have been produced for their benefit. That is what I am urging you to do.

V. CONCLUSION

All Christians are called to witness to their faith, but that does not only mean witnessing to those who do not know the Gospel. All of us have things we know that those around us do not and we have a responsibility to share our knowledge with people who need it and do not know where to find it. You, the Maronite Church, have in your bones and at your fingertips, riches of devotion and theology that the West knows nothing about, as I saw so vividly a month ago in Chicago. You have the power to offer these riches to your Christian brothers and sisters, and you know that if you do not make that effort, these things will never be known to them. This is a heavy responsibility, but it is one all Christians share in common, in their own ways. If you will do your part, it would offer a great deal to those around you who thirst for real insight into the mystery of God and real witness to His presence. These are things that Syriac Christianity has in abundance. On behalf of my fellow Christians of the West, I would like to say that I hope you will unlock your treasure chest and give us some of your riches. You will not feel any lack as a result of your generosity, and our benefits will be immeasurable.

____________________________

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beggiani, Seely. Introduction to Eastern Christian Spirituality: The Syriac Tradition, Scranton, PA: University of Scranton Press, 1991.

Brock, Sebastian and Susan Harvey. Holy Women of the Syrian Orient, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.

Brock, Sebastian, Trans. SOGIYATHA Syriac Dialogue Hymns, The Syrian Churches Series, edited by Jacob Vellian, Vol. XI Kottayam, Christmas 1987, pp. 14-20.

Brock, Sebastian, Trans. St. Ephrem the Syrian, Hymns on Paradise, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press: Crestwood, NY, 1990.

Brock, Sebastian, Trans. The Syriac Fathers on Prayer and the Spiritual Life, Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications, 1987.

Budge, Kt. Sir E.A. Wallis. The Monks of Kublai Khan Emperor of China, London: The Religious Tract Society, 1928.

Foster, John. The Nestorian Tablet and Hymn, London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, (no date).

Gillman, Ian and Hans-Joachim Klimkeit, Christians in Asia before 1500, Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Gillman, Ian and Hans-Jocachim Klimkeit. Christians in Asia before 1500, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Hansbury, Mary, Trans. Jacob of Serug, On the Mother of God, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press: Crestwood, NY, 1998.

Hansbury, Mary, Trans. St. Isaac of Nineveh, On Ascetical Life, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press: Crestwood, NY, 1989.

Mathews, Edward and Joseph Amar, Trans. St. Ephrem the Syrian, Selected Prose Works, Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 1994.

Mc Vey, Kathleen. St. Ephrem the Syrian, Hymns, Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1989.

Moffett, Samuel Hugh. A History of Christianity in Asia Volume I: Beginnings to 1500 Harper: San Francisco, 1992.

Moffett, Samuel. A History of Christianity in Asia, Volume I: Beginnings to 1500, Harper Collins, 1992.

Moffett, Samuel. A Short History of Syriac Christianity to the Rise of Islam, Scholars Press, 1982.

Price, R. M., Trans. A History of the Monks of Syria, Kalamazoo, Michigan: Cistercian Publications: 1985.

Rowell, Geoffrey. “‘Making [the] Church of England Poetical’ Ephraim and the Oxford Movement,” Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies [http://syrcom.cua.edu/Hugoye/Vol2No1/HV2N1Rowell.html] Vol. 2, No.1, January 1999.

Stevenson, Jane. “Ephraim the Syrian in Anglo-Saxon England,” Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies [http://syrcom.cua.edu/Hugoye/Vol1No2/HV1N2Stevenson.html] Vol. 1, No. 2, July 1998.

Whitfield, Susan. Life Along the Silk Road, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 1999.

Zibawi, Mahmoud. Eastern Christian Worlds, The Liturgical Press: Collegeville, Minnesota 1995.