PART II By Guita Hourani

I. INTRODUCTION Marina was a woman who disguised herself as a man to join her father, a layman who gave up everything after the death of his wife and became a monk at the Monastery of Our Lady of Qannoubin in the Qadisha Valley of Lebanon. [Henceforth in the text whenever chronologically or contextually appropriate in relating her story, Saint Marina will either be referred to as "Marina" (feminine), or as "Marinos" (masculine).] Father Marinos, as Marina was known, had been falsely accused of fathering a child. When confronted, Marinos said nothing in her own defense, and so the abbot expelled her from the monastery. Marinos, having been believed of "fathering" the child, was given it to raise. Whether at the monastery door or in a small adjacent grotto, Marinos spent her time praying, begging forgiveness to return to the monastery, living ascetically, and raising and teaching the child. A few years later, the Abbot allowed Marinos to return to her cell at the monastery, but imposed strict terms and conditions upon her. Marinos accepted and lived an even more ascetic life than previously, until the day she died. It was only then that the Abbot, the monks, and the people of the surrounding villages knew that Marinos was a woman who obviously had been falsely accused. They lamented her, repented their own sin against her and revealed to everyone the false accusation which had destroyed the Monk Marinos' reputation. The mother of the child and her father, the main accusers, wept in repentance and asked forgiveness. Marina became a venerated saint in Mount Lebanon and from there her veneration spread to Jerusalem, Constantinople, Italy, Venice, France and many other places. Her story has been told in many languages. Today she is mainly honored in Lebanon, Cyprus, and in Venice, Italy. II. VENERATION OF MARINA A. The Grotto of Saint Marina is located near the Monastery of Our Lady of Qannoubin It is believed that the saint was entombed in this grotto in the eighth century. (Goudard 1908: 311) Upon his visit to Qannoubin in the early part of the eighteenth century, De La Roque described the grotto as follows: "It is only at 100 meters from Qannoubin that we see the Grotto of Saint Marina the Virgin. It is formed by nature alone in a great rock which we reached conveniently. In the past, one would enter through a natural opening in the rock; but now there is a wall and a small door which remains closed because the Liturgy or Mass is celebrated daily and the altar items are left there. The Grotto is approximately 15 feet long, between 8 and 10 feet wide, and the height of a good-sized man at the altar. Behind the altar, the height declines. The Maronites' devotion to this place is so great that their Patriarchs have chosen the land in front of it for their sepulcher[s]." (De La Roque 1722: 59-60) I visited the Monastery of Our Lady of Qannoubin and the grotto of Saint Marina on September 10, 1999. The monastery is now occupied by the Antonine Order of nuns from June to mid-September. The monastery ceased to be the See of the Maronite Patriarch around 1823 when a new monastery was built in Diman to serve as an all-year-round residence for the Bishop of Bcharre and a summer residence for the Maronite Patriarch. The monastery as well as the devotion of Saint Marina have both suffered from shifting the See elsewhere, first to Diman and then to Bkerke. After a visit with the nuns and my former High School Principal, Mother Domenique Halaby, who was on a spiritual retreat at the monastery, the Superior of the monastery, Sister Mona 'Awad, accompanied me from the monastery to the grotto. The path still consists of sand. A few feet before the grotto's wall, there is an old tree and a small plot of land surrounded by stones on the right and the cliff and valley on the left. The Maronite Patriarchs used to be buried in this exact lot. In the background is a stone wall and a blue wooden door which leads to the chapel of Saint Marina. According to Le Chevalier D'Arvieux, who visited the grotto in 1660, "the grotto was changed to a chapel which was enlarged and embellished as much as the place and the poverty of these religious allowed." (Moubarac 1984: 852)

The mausoleum holds the remains of fifteen of the twenty-four Maronite Patriarchs who served when Qannoubin was the See of the Maronite Patriarchate from 1440 to 1823. It was during the Mameluke era that Patriarch Youhanna Al Jaji (John of Jaj) was forced to leave his see in Mayfouq and take refuge at Our Lady of Qannoubin.[1]

“This blessed mausoleum was erected in the year 1909, during the days of His Beatitude Mar Elia Boutros Patriarch of Antioch and All the East, where resting with the hope of the holy resurrection our Fathers the Blessed Patriarchs whose names are herein listed for their memory and for eternity: John of Jaj (1440-1445) Jacob Eid of Hadeth (1445-1468) Joseph Hassan of Hadeth (1468-1492) Semaan Hassan of Hadeth (1492-1524) Moussa Saade Al-Akari (1524-1567) Michael Rizzi of Bkoufa (1567-1581) Sarkis Rizzi of Bkoufa (1581-1596) Joseph Rizzi of Bkoufa (1596-1608) John Makhlouf of Ehden (1608-1633) Georges Omaira of Ehden (1633-1644) John Bawab of Safra (1648-1656) Etienne Septhen Douaihi of Ehden (1670-1704) Gabriel of Blaouza (1704-1705) Joseph Tayan of Beirut (1796-1808) Helou of Ghosta (1808-1823) Patriarchs Joseph Hobaish (1823-1845) [whose See was in Bkerke] Joseph Ragi El Khazen (1845-1854) [whose See was in Bkerke] The remains of the righteous are joyful for they loved the Truth” Today, the grotto serves as a shrine. People of the Holy Valley make pilgrimages to the grotto on Saint Marina's feast day, July 17, when Mass is celebrated in reverence of this once famous saint. B. The Grotto Shrine of Saint Marina in Qalamoun, Lebanon On the road from Jbeil to Tripoli in an area called Qalamoun, the Grotto of Saint Marina stands, stately guarding the sea. This grotto shrine was famous for the beautiful frescos that once ornamented it. After having read about it and armed with Father Youhanna Sader's book – Painted Churches and Rock-Cut Chapels of Lebanon, I climbed the slopes to the grotto shrine in the early part of January 1999. The book contained ample photos and descriptions of the paintings of the grotto and showed the grotto's roof, apparently washed by waves of sea water for centuries past and showing the imprint of fossils. I saw that there was nothing left of what Father Sader has described in his book. Bare walls were partly blackened and encrusted with mold caused by the rain, but there were no longer any frescoes. I was greatly saddened and disappointed because another historical monument in Lebanon had forever disappeared. Although the original paintings cannot be recovered, we are thankful that two foreign scholars, Charles Virollaud and Charles Brossé, examined these frescoes between 1922 and 1926, and left written descriptions of the lost images. From their writings, the reader learns that two different saints were named Marina. From the now lost paintings, they identified Marina of Qannoubin and a different Marina who was depicted with millet. (Fiey 1978: 34) 1. Description of Charles Virollaud Virollaud wrote that "the complete length of these paintings is 8.40m and their height must have originally reached about 3m. However, unfortunately all the lower part has disappeared, the rock having been cut away. Furthermore, the paintings have suffered greatly from the weather and even worse, the faces of Christ and the saints have been intentionally erased. The paintings are actually unique documents in Syria and one has to go as far as Abou-Gosh in Palestine to see paintings of this style. The inscriptions accompanying and explaining these paintings are sometimes in Greek, but more often in Latin." (Virollaud 1924: 117-118) 2. Description of Charles Brossé Charles Brossé has written an analysis of the fresco which he saw at the grotto of Marina in Qalamoun. His description is our only tangible evidence of what once existed. Brossé states that the massive rocks have an opening into a cliff of gray limestone; and that the village of Deddeh is situated above the hill. He describes the grotto as "a large cave that extends for about 20 meters, mostly on a horizontal plane. It is 7 meters high and 5 meters deep, and the entrance lies some fifteen meters up the cliff wall. The rounded rear part of the grotto of Marina carries the remains of some paintings representing various subjects. Unfortunately, the effect of running water has been to remove most of the panels of paintings on the left. More damage has been done by the Muslims who live in this area, who have erased or hammered the faces of all the figures without exception." (Brossé 1926: 118) Youhanna Sader dates these frescoes to the 13th century A.D. (Sader 1997: 146-164) According to Brossé, attempts at restoration also caused serious damage. It seems that the person who intended to restore or replace the paintings, cut away a lower rock section of approximately 1.50m wide and 2.20m high, effectively removing about four mural panels. (Brossé 1926: 118) According to local tradition, women of the area who lack milk or suffer other nursing problems visit her grotto and pray, light candles, and even bless themselves with water which flows there. They believe that they will be blessed with milk and therefore some refer to this shrine as the "Milk Grotto." (Fiey 1978: 33) C. Saint Marina's Ancient Sepulcher, South Of Amioun's Seraglio I also paid a visit to the sepulcher, south of the Seraglio of Amioun, which is said to be the grotto of Saint Marina. I found no written or oral reference to link this grotto to Marina of Qannoubin. I found a reference to Saint Marina of Antioch. D. The Church and Village Of Ayia Marina In Cyprus The village of Ayia Marina is located south of Nicosia, the capitol of Cyprus, and is about 250 meters above sea level. Its Maronite people originated from the Qadisha Valley in Lebanon. Upon settling in this part of Cyprus, they founded a village and named it after their patron saint, Marina of Qannoubin. The first wave of Maronites to settle in Cyprus came from Syria Seconda in the eighth century (Cirilli 1898: 5) because of the Islamic conquest and the inter-Christian rivalries between the Jacobites and the Byzantines which inflicted violence upon the Maronites. (Dib 1971: 51-52) Another wave of emigrants followed in the tenth century after the destruction of Saint Maron's Monastery on the Orontes River. (Dib 1971: 52-53) However, the later migrations originated from northern Lebanon where the Maronites were concentrated. The migration first occurred when Guy de Lusignan purchased Cyprus at the end of the twelfth century and invited all the knights, honorable fighters, and the bourgeoisie who wanted land to come. (Cirilli 1898: 6) Another exodus took place with the defeat of the Crusaders in Tripoli in 1298. (Dib 1971: 65, 77). The Maronites of Cyprus were served by their own monks who most probably brought in the same type of devotions and religious practices. In Florence, Laur. - Plat. I, 56 f° 7v Canon IV states that in 1153 A.D., a monk from the Monastery of Qozhaya in the Qadisha Valley was sent by Maronite Patriarch Peter to preside over the Monastery of Saint John of Kouzband in Cyprus. The original document is to be found in the Rabbula Gospels (586 A.D.). "On the 8th day of September of the year 1465 to the Greek [1153/1154 AD], came to me, Boutros [Peter] Patriarch of the Maronites, presiding over the See of Antioch in the Monastery of Our Lady of Mayfouq in the Valley of Ilige, the young monk Asha'ia [Isaac] of the Monastery of Qozhaya, and I made him Superior of the monks of the Monastery of Saint John of Kouzband in the Island of Cyprus. [This was done] in accordance with the letter written in the hands of the monks [of that monastery], which he had brought to me. [The monks] are the Monk Sham'oun, the Monk Habdouk, and the Monk Michael, to God be glory, Amen." (Leroy 1964: 146) This document demonstrate that there was a Maronite colony to be served in Kouzband, Cyprus; that the monks of Saint John knew the monks of Qozhaya in the Qadisha Valley since they have asked for the monk Asha'ia by name; and that they were under the authority of the Maronite Patriarch who resided in Lebanon. This also leads us to infer that they have followed the same religious practices, including the veneration of saints. Maronites and other groups, even to this day when they migrate, take the name of their village's patron saint with them to their new settlement. The people of Ayia Marina have done the same. Their church and even their village are to this day known by the name of their beloved saint. Reverend Jérôme Dandini, the Envoy of Pope Clement VII, visited the Maronites of the island during his papal mission to the Maronites of Lebanon in 1596. Dandini stated that the Cypriot Maronites were all under the authority of the Maronite Patriarch whose See was in Lebanon. He also declared that at times there was at least one priest for each parish and that sometimes there were eight, as there had been in Metoschi. He named the 19 Maronite villages left in Cyprus: Metoschi, Fludi, Saint Marina, Asomatos, Gambili, Karpasha, Kormakiti, Trimitia, Casapisani, Vono, Cibo, Ieri, Crusicida, Cesalauriso, Sotto Kruscida, Attalu, Cleipirio, Piscopia, and Gastria. However, when he visited Cyprus in 1596, he learned that there were not many Maronite clergy left, that many Maronites had either fled or apostatized and that there were only ten parishes, the most important being Saint Marina, Kormakiti and Asomatos. (Dandini 1656: 23). Ayia Marina is described in the early part of this century and before the 1974 Turkish invasion as "partly Maronite and partly Turkish. The only monastery still in occupation by Maronite monks is Saint Elias, near Saint Marina and about six miles from Karpasha." (Bardswell 1939: 307) Every year on July 17th the feast of Saint Marina, the Maronites of Ayia Marina celebrate with a solemn Mass and the blessing of the village with a procession with the icon of Ayia Marina through the narrow roads of the village. Following the liturgical celebration, a regular festival takes place in the center of the village with food, beverages, and singing. At the start of the Turkish invasion of the Island of Cyprus in 1974, Ayia Marina village had two churches. One church was named after Saint Marina and believed built in the 1400s. A second church was built in 1971. The majority of its inhabitants were Maronites (about 500 Maronites and 100 Turks). The village is now a military camp, completely under Turkish occupation. On a small hill overlooking the village was the monastery of Saint Elias. It belonged to the Lebanese Maronite Order of Monks and is also under occupation. The Maronites of Ayia Marina, like the rest of those who left their villages during the invasion, don't have the right to return or to land inheritance or ownership. Which means that upon the death of the current owner, the land becomes the property of the Turkish Government. III. ICONOGRAPHY

The oldest known icon of Marina of Qannoubin must be the one that De la Roque mentioned in his book and which Goudard described in his book as "a painting representing the saint in the habit of a monk serving bread and milk curd to the infant who was not hers." (Goudard 1908: 313) We know nothing about this icon. Nobody knows if this icon is somewhere else, was thrown into an attic where it is either damaged or collecting dust, or perhaps given as a gift to one of the European envoys. During my visit to the grotto, I did not find this painting. Rather, I was told about another painting that the sisters had sent for restoration because it was damaged by a hole caused by pilgrims who took small pieces as relics. A few days later, I visited Our Lady of Deliverance, "Saidet el-Khalass", in Ain Alaq Convent of the Antonine Nuns in the Maten area. The icon was being restored there. I saw that it showed Marina standing, dressed in a monk's black habit with a cowl on her head and a belt around her waist. She gazes upon the child whom she is raising. Her left hand is placed on her breast, while her right hand is extended lovingly toward the child. Marina looks Semitic in the painting, but the boy returning her gaze appears to be more European because he has curly, blond-reddish hair. The painting is not dated or signed. I asked about the icon's return to Qannoubin, and was told that it would be returned to the grotto when it could be safely displayed and not suffer damage again. From my first look at the painting, I noticed it contained an inappropriate symbol that showed that the painter had paid little attention to the story of Marina. He had painted her wearing the symbol for chastity, a monastic belt, which would have been taken from her immediately upon expulsion from the monastery. The painting needs to be studied thoroughly by experts to determine its origin, the identity of the painter, the era in which it was painted, and the symbols used. B. The Frescoes of Saint Marina's Grotto Shrine in Qalamoun Charles Brossé's 1926 description of the frescos of Marina's grotto shrine in Qalamoun is the only written record of what once existed. Brossé saw eight meters of painted surface to the right of the grotto (decorated originally with five paintings within two large panels on each side of a narrow central panel). The saints represented were identified in Greek script. (Brossé 1926: 118) The originals were painted in solid colors. All the figures, except the one in the center, are life-size. 1. Panel A Panel A is the figure of a woman carrying a mallet in her right hand. An inscription in Greek identifies her as Agia or Saint Marina. (Brossé 1926: 120) However, this is not a painting of Saint Marina of Qannoubin. 2. Panel B Panel B, two meters wide, was almost entirely destroyed when Brossé examined it. It represents the Annunciation with the Archangel Gabriel on the left announcing the good news to the Virgin Mary, standing at the right. (Brossé 1926: 121) 3. Panel C Panel C was only 0.50m wide and 1.40m high. It is apparently the portrait of Zacchaeus, the chief publican of Jericho. (Brossé 1926: 121) 4. Panel D Panel D was 1.82m wide and about 1.15m high. It is a Diesis representing Jesus the Pantocrator with the Blessed Mother to His right and Saint John the Baptist to His left. (Brossé 1926: 119-122) 5. Panel E Panel E is composed of one single image, 2.28m wide, which disappeared under a later restoration. It is the figure of Saint Demetrius mounting, while using a lance to stab the prostrate Nestor. (Brossé 1926: 123) 6. The Later Paintings According to Brossé, Saint Demetrius' panel was covered over with a light plaster layer and divided into two blocks with eight, almost equal panels upon which new subjects were painted. The cycle progresses from left to right, first in the upper block, then in the lower one. These eight compositions represent eight episodes in the life of Saint Marina of Qannoubin. Panels F, G, H, K, as numbered by Brossé, illustrate the first part of Marina's life until the death of her father. Panel F shows Marina as a young girl when her father entered the monastery. In Panel G, Marina's father weeps before the abbot and declares that he has left his child behind. Panel H shows Marina being presented to the Abbot with her father at her side. Panel K portrays Marina at the bedside of her dying father.

The information above --about these frescos of Saint Marina's grotto in Qalamoun-- seems to prove that the Marina depicted with the symbolic mallet is not Marina of Qannoubin. However, the eight panel frescoes are depictions of her passion. Today, unfortunately, none of the Qalamoun frescos survive. It is only through Brossé's work that future generations can savor this patrimony. C. Saint Marina As Painted by Saliba Duwaihi The most famous icons or portrayals of Saint Marina were created by the renowned Maronite painter, Saliba Duwaihi. They are Saint Marina's mural at Our Lady of Diman; a painting of the saint in the possession of Marina Fouad Ephrem Al-Bustani; and a painting believed to be in the possession of Duwaihi's widow.

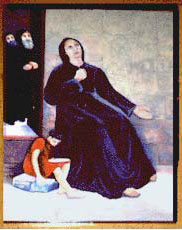

The mural at Our Lady of Diman, the summer residence of the Maronite Patriarch, is one of many murals covering the ceiling of the beautiful cathedral. This Sistine Chapel of Lebanon was painted by Duwaihi in the late 1930s. In 1988, the paintings of Saint Marina and of Saint Stephen, the First Martyr, were scraped and removed from the walls because of irreparable damage caused to them by water leakage in the Church. Their removal and loss angered Lebanese art critics and historians. Completed by Duwaihi in 1937, the two original oil masterpieces were painted directly on calcic walls without any insulation material and little regard for proper mural painting techniques. Because no way was known to prevent or impede the water damage, the complete destruction of the murals resulted. Following the critical reactions, His Beatitude the Maronite Patriarch Sfeir commissioned the creation of exact replicas of the two works on canvas, rather than as murals, to prevent future damage by moisture or water. Artist George Al-Zaatini, who studied under Saliba Duwaihi, was chosen to reproduce the subjects of the murals as true to Saliba’s original masterworks as possible. In an atmosphere of jubilation and satisfaction in June 1999 -- less than one year after His Beatitude commissioned the replacements -- the new paintings of Saint Marina and Saint Stephen were installed in Our Lady of Diman Church. 2. The Bustani Family's Painting of Saint Marina Fouad Ephrem Al-Bustani named his daughter Marina in honor of the Saint. He also wrote a book about Saint Marina entitled: Marina, the Lebanese: Monk of Qannoubin. He published it in Beirut in 1983. The cover of the book was a photo of an oil on canvas painting of Saint Marina of Qannoubin by Saliba Duwaihi. The painting depicts Marina in a black habit and cowl, seated at the door of the monastery with her eyes raised to Heaven, with her right hand on her breast and her left hand extended in supplication. To her right, the boy sits with his head leaning toward her. He appears to be carrying a prayer book in his lap. Behind them, two monks stand in the open monastery door looking toward Marina and the child. Marina's face is most expressively devout. The painting is now in the possession of Marina Al-Bustani, daughter of Fouad Ephrem Al-Bustani. D. The Icon of Ayia Marina of Cyprus The image of Saint Marina in Cyprus is the one presented in the small photo held by Mrs. Ascott, the iconographer of the Maronite Icon Atelier in Nicosia, Cyprus, and by the Abbess of the Antonine Nuns in Nicosia and the author of this article. This image of Ayia Marina, the saint, is associated with the village and is engraved in the collective memory of its inhabitants.

In the new icon, which is oil on canvas, Saint Marina is seated on a

rock inside her grotto. Behind her are visible the Holy Valley of Qadisha

and its jewel - Our Lady of Qannoubin Monastery. The Saint is wearing a

habit with a traditional Near Eastern headdress. Deep in thought, she is

holding an infant on her lap and is carrying a bowl of milk in her left

hand. A halo encircles her head. The infant is reaching toward the bowl

with both hands. Marina's name is inscribed in Syriac and Greek. One day

this icon will hang in the apse of Saint Marina's Church in the village

of Ayia Marina, Cyprus. For the time being, the icon must continue to wait

along with the villagers the end of the Turkish occupation. The new icon of Saint Marina in Cyprus. Photo courtesy of the Maronite Bishopric of Cyprus Sacred Art Atelier, Nicosia, Cyprus, February 2000 A common thread in all her images, whether paintings, frescoes, icons or stained glass, is that Saint Marina is always portrayed in a habit as woman monk with a child in a monastery setting. IV. SUMMARY Marina's story is the only reference known to us of Maronite monastic women in the first Millennium. The passion of Saint Marina is rich in Christian virtues and lessons. Marina is a perfect ascetic; she is obedient, prayerful, humble, austere, and forgiving. She is a model monk. She is described as a strong person who persevered under harsh physical and emotional circumstances in order to follow the life she had chosen. She endures in silence both the cruel judgment of people and the hard conditions of ascetic living. In life, she was a living martyr; in death, she was a saint! Although she is still listed in the Maronite synaxarium with her feast day celebrated on July 17, Marina has been overshadowed by more recent Maronite and Western saints with the passage of time. Despite that, Marina lives on in the conscience of the Maronite people as a woman who --unjustly accused and judged -- was faithful to her monastic vows, and prayed for and forgave her accusers. Fortunately, the descendents of the village of Ayia Marina in Cyprus revere her as ever they have. Saint Marina is the patroness of Maronite Patriarchs and is the traditional

benefactress of nursing mothers.

Bibliography Al-Bustani, F. A. Marina al Lubnaniat Rahibat Qannoubine (The Lebanese Marina: Monk of Qannoubine) in Arabic, Beirut, 1983. Bardswell, M. A Visit to Some of the Maronite Villages of Cyprus, Eastern Churches Quarterly, Vol. III, N° 5, 1939, pp. 304-308. Brossé, Ch. L. Les Peintures de al Grotte de Marina près du Tripoli, Syria, Vol. VII, 1926, pp. 30-45. Cirilli, J. Les Maronites de Chypre, Cyprus, 1898. Dandini, J. Missione Apostolica al Patriarca e Maroniti et Monte Libane, e sua Pellegrinazione a Gierusalemme, Cesena, 1656. De la Roque, J. Voyage de Syrie et du Mont Liban, Paris, 1722. Dib, P. History of the Maronite Church, translated by Seely Beggiani, Detroit, 1971. Duwaihi, E. Tarikh al-Azminat, Ed. B. Fahd, Dar Lahd Khater: Beiurt, 2nd edition, 1983. Fiey, J. De Quelques Saints Vénérés au Liban, Proche Orient Chétien, Vol. IX, 1904, pp. 18-43. Goudard, J. La Sainte Vièrge au Liban, Paris, 1908. Leroy, J. Les Manuscrits Syriaques A Peintures Conservés dans les Bibliotèque d’Europe et d’Orient, Paris , 1964. Mahfouz, J. Precis d’Histoire de l’Eglise Maronite. Imp. St. Paul, Kaslik, Lebanon, 1985. Mouawad, R. Sainte Marina: Une Moniale dans la Vallée de la Qadisha, Acte du Colloguq-Patrimoine Syriaque VI, Antelias, Lebanon, 1998, pp. 271-285. Moubarac, Y. Patrologie Oriental: Domaine Maronite, Tome II, Volume I, Beyrouth, Liban, 1984. Niero, A. Santa Marina di Bitinia: Profilo Biografico, Venice, Italy, 1998. Sader, Y. Painted churches and Rock-Cut Chapels of Lebanon, Dar Sader: Beirut, 1997. Sfeir, P. Les Ermites dans l’Église Maronite: Histoire et Spiritualité, Bibliothèque de l’Université Saint-Esprit, Lebanon, 1986. Virollaud, Ch. Les Travaux Archéologiques en Syrie en 1922-1923, Syria, Vol. V, 1924, pp.117-126. [1] Because of Mameluke obsession with the Franks and continual fear that they would return to the Holy Land and the coast of Lebanon. The Mamelukes kept "a jealous eye on the relationship of their Christian subjects with all foreign countries. Every attempt at relations with the former masters of Syria was considered unpardonable treason, a plot against the security of the State." (Dib 1971: 68) So when Brother John, Superior of the Franciscans in Beirut, who was the Patriarch's envoy to the Council of Florence at the invitation of Pope Eugene IV, returned from his mission to Lebanon, the Mamelukes persecuted the Maronite laity and clergy, burned the Monastery of Our Lady of Mayfouq and pursued the Patriarch himself. When Patriarch Al Jaji moved to Qannoubin monastery, it became the new Patriarchal See. (Dib 1971: 68) | Back to text | [2] Nine Patriarchs who served when the Patriarchal See was in Qannoubin are interred elsewhere for various reasons being it sudden death, burial in family tombs, or in monasteries. These Patriarchs are: Joseph Haleeb of Akoura (1644-1648) entombed at Saint Peter Church in Aqura, Georges Rizkallah of Bseb’el (1657-1670) buried at Saint Arthem Monastery (Mar Challita) in Moqbes-Ghosta, Jacob ‘Aouad of Hasroun (1705-1733) buried at Saint Arthem Monastery in Moqbes-Ghosta, Joseph Dergham El Khazen of Ghosta (1733-1742) buried at Saint Elias Church in Ghosta, Simon ‘Aouad, (1742-1756) buried in Jezzine at Our Lady of Mashmoushe Monastery, Tobia El Khazen (1756-1766) buried at Our Lady Church in ‘Ajaltoun, Joseph Estephan (1766-1793) buried at Saint Joseph El-Hosn Monastery in Ghosta, Michael Fadel of Beirut (1793-1795) entombed at Saint John the Baptist in Hrash, and Philip Gemayel of Bikfaya (1795-1796) entombed at our Lady of Bkerke. In 1823 the Patriarchal See moved from Our Lady of Qannoubin to Our Lady of Diman. (Mahfouz 1985: 51-65) | Back to text | |