Guita G. Hourani

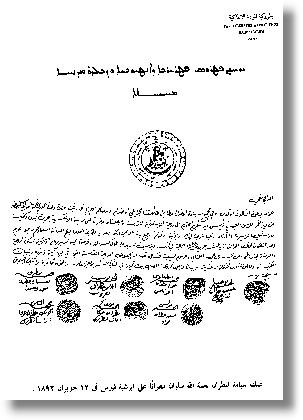

This article addresses the reasons behind the Maronite migration to Cyprus from the eighth century to the British occupation, and reads into their history from available manuscripts. History narrates four major migrations of the Maronites to the Cypriot Island. The first exodus occurred in the eighth century with the fleeing of the Maronites from the plains of ancient Syria to Mount Lebanon. The second transpired upon the destruction of the Monastery of Saint Maron on the Orontes River toward the end of the tenth century. The third migration came at the beginning of the reign of the Lusignan Dynasty at the end of the twelfth century. The fourth transmigration was engendered by the defeat of the Crusaders in Tripoli toward the end of the thirteenth century. The article also examines the Cypriot Maronite situation during the reigns of the Latins and the Ottomans. It also brings to light the reasons behind the demise of the Maronite colony in Cyprus, which at times numbered sixty villages but was reduced to four by the end of the Ottoman reign. Brief History of Cyprus According to the New Testament, the first evangelization of Cyprus occurred around the year 44 A.D through Saint Paul the Apostle and Saint Barnaba, a native of the island (Act of Apostles IV, 36; Act XI, 20; Act. XI, 19; Act XIII, 4 and Act XII, 5-12). Saint Barnaba was martyred in Cyprus and is believed to be buried there (Palmieri 1905: col. 2425). The island blossomed with Christian spirit until the Islamic conquest, which began in 632 AD with the invasion of the island by the Caliph Abou-Bakr, followed by the domination of Caliph Moawiat between 647-648. In the ninth century, the army of Haroun al-Rachid ravaged the island, committing unimaginable atrocities and destroying churches and monasteries (ibid. 1905: col. 2432, Mc Guire 1967: 568). By the tenth century, Christianity flourished again on the island under the reign of Byzantium. Nevertheless, the Byzantines managed to inflict suffering upon all the Cypriots, especially through mal-administration and violence (Palmieri 1905: col 2434, Mc Guire 1967: 568) and thus paved the way for Latin domination. Cyprus fell into the hands of the Latins in 1191 upon the landing of the army of Richard the Lionhearted, who was enroute to the Holy Land. The island was then sold to Guy de Lusignans, titular king of Jerusalem. This domination lasted four centuries and included the reigns of the Lusignans (1192-1489) and the Venetians (1489-1571). The era was characterized by violence between the Greeks and Latins, and the Western feudal system adopted by the rulers caused internal rivalries, abuse of power and corruption (ibid. 1905: cols. 2433-2442, 2461-2462; ibid. 1967: 568-569). Cyprus fell to the Ottomans in 1571. From this date and until 1878, the history of Cyprus can be characterized as a period of uninterrupted interior battles of ambition, as well as oppression, persecution and exorbitant taxation (Cirilli 1898: 14-18, Palmieri 1905: cols. 2442-2443). In 1878 the British landed on the island to defend Turkey against Russia’s expansionist policy in Asia Minor. However, Britain annexed the island and remained its occupying force until the island's independence in 1964. The epoch was marked by violence, terrorism, guerrilla warfare and conflict between the Greek and the Turkish populations of the island, as well as by the struggle for independence (McGuire 1967: 570). The island's independence did not last long, however. The Turkish army invaded Cyprus in 1974, causing its division, and no peace has been reached since then, despite several attempts at conflict- resolution and peace negotiations. The Earliest Maronite Exodus to Cyprus The history of the Maronite-Cyprus relationship is long and painful. In four principal migrations between the eighth and the thirteenth centuries, Maronites moved to Cyprus from the ancient territories of Syria, the Holy Land and Lebanon. Tradition narrates that the first group of Maronites immigrated to Cyprus simultaneously with the Maronite migration to Lebanon in the eighth century (Cirilli 189: 5). This exodus was caused mainly by the Islamic conquest and the inter-Christian rivalries between the Jacobites and the Byzantines, which inflicted violence against the Maronites (Dib 1971: 51-52). The second major migration followed the destruction of Saint Maron's Monastery on the Orontes River in Apamea around the year 938 A.D., which led to the transfer of the Maronite patriarchal residence to Mount-Lebanon (Dib 1971: 52-53; Assamarani 1979: 17). Little information is available to confirm or refute the chronicle of the two migrations. The third Maronite migration occurred upon the purchase of Cyprus by Guy de Lusignan towards the end of the twelfth century (Cirilli 1898: 6). The fourth occurred at the end of the thirteenth century with the defeat of the Crusaders in Tripoli and the Holy Land (Dib 1971: 65, 77).

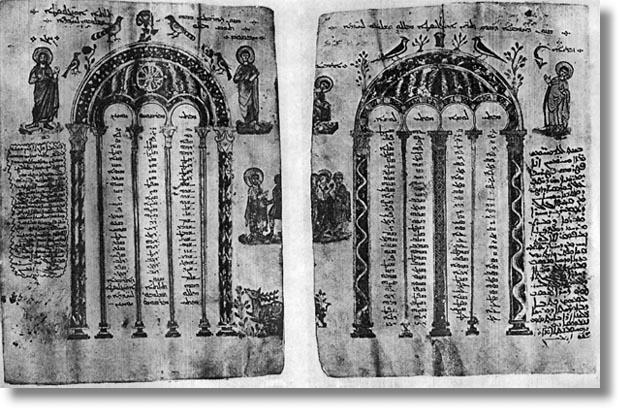

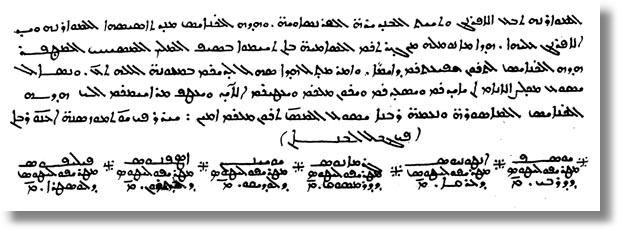

Available historical documents confirm that the Maronites were an active

community in Cyprus prior to 1192 A.D. The oldest manuscript accessible

in this regard dates to the twelfth century -- Syriac Manuscript Vat. Syr.

118 f° 262 r of the Vatican Library. This manuscript contains a handwritten

inscription in Syriac, translated as follows:

Three other manuscripts substantiate the above statement. Two, Florence

Laur.- Plat. I, 56 f° 7 v. Canon IV and Florence Laur.- Plat. I, 56

f° 8 r. Canon V, are to be found in the Syriac Manuscript of the Laurentine

Library of Florence known as the Rabbula Gospels (586 AD) and one is inscribed

in the Syriac Manuscript Vat. Syr. 118 f° 261 v of the Vatican Library.

They are translated and herein presented respectively:

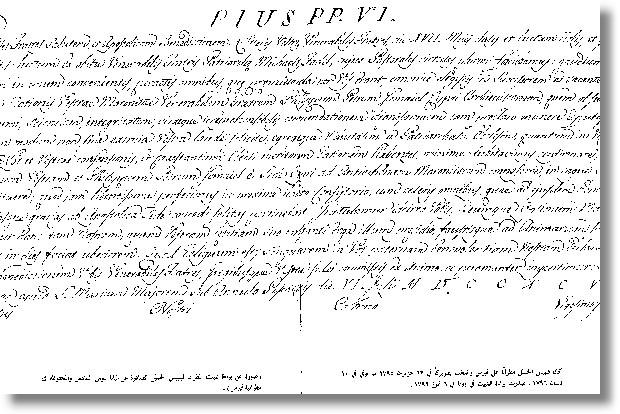

The above manuscripts ascertain that the Maronites had active communities in Cyprus prior to the twelfth century. They also certify that these communities were spiritually and ecclesiastically shepherded by their own Maronite priests, that they were in communion with the faith of their brothers in Lebanon and that the lay and clergy were all under the authority of the Maronite Patriarch who resided in Lebanon. It is to be noted that traditionally a monastery would not have been established on the island unless there was already a community to serve. The Maronites under the Reign of the House of Lusignan (1192-1489) Upon his reign over Cyprus in 1192 AD, Guy de Lusignan announced that those cavaliers, warriors or bourgeoisie who wished to have fief or land should come to him (Cirilli 1898: 7). Consequently, many Christian communities journeyed to Cyprus, among whom were some Armenians, Copts and Maronites. King Guy gave these communities many quarters in the city of Nicosia, where they built houses and churches (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462; Cirilli 1898: 7). The Maronites "did not mix with the inhabitants of the island. They preferred the high places north of Nicosia, and there, in that setting which recalled for them their mountains of Lebanon, they lived, preserving their culture and guarding their simple and familial customs. Encouraged by the kings of Cyprus, their colony became prosperous and relatively numerous: it counted up to 72 villages" (Dib 1971: 65). The Maronite immigrants constituted the largest community in number after the Greeks on the island and were granted many privileges by the kings of Cyprus (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462; Cirilli 1898:7 Dib: 1971: 65). These privileges were most probably due to the fact that the Maronites were Catholics, that they had an impressive record of helping the Crusaders since their first expedition and could be counted on in time of need (Cirilli 1898: 7). There is no accurate data available as to the number of the Cypriot Maronites during the reign of the Lusignans. What we know from available sources is that in 1224 AD and during the reign of Henri I de Lusignan, the Maronites settled in and established 60 Cypriot villages. We also know from the same references that they provided Saint Louis, the King of France, with a contingent of 5,000 men for his expedition to Damietta in Egypt in 1250 (Cirilli 1898: 7-8; Hill 1972: 143). The total number of the Maronites is not known. Some say it was 800,000 and others say 180,000 strong (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462), but these figures are implausible (Hill 1972: 144). However, it is probable that, since they were the largest community after the Greek, the Cypriot Maronite population must have been sizeable if it could afford providing 5,000 men for the expedition to Egypt. An average family in the Middle Ages was composed of five members and an average community of 300 people, which would make 60-72 Maronite communities average a total of at least 18,000 to 21,600 people. Many Christian communities made Cyprus their asylum, especially when the Holy Land fell into the hands of the Muslims (Assamarani 1979: 22, Dib 1971: 65). As for the Maronites, their migration to the island increased or decreased according not only to the socio-political situation in their countries of origin, but also to that of Cyprus as well. The reasons behind the Maronite migration to the island were diverse. At times it was because of persecution, such as during the 1293 massacres in Damascus (Assamani 1979: 22), or because of the submission war launched by the Mamluks between 1292 and 1307 against the Maronites mainly in Kisserwan (Awwad 1950: 33-36), or because of the persecution and tyranny of the Ottomans during their reign (1571-1878) (Assamarani 1979: 23, Dib 1971: 177). Under the Lusignans, the Maronite Bishopric of Cyprus included only the island. The Maronite Bishop of Cyprus resided on the island with his flock. In fact, the Bishop's see remained on the island until the end of the sixteenth century when Cyprus fell into the hands of the Ottomans. Afterwards, the Bishop resided in Lebanon and visited the island on occasion as a legate of the Patriarch (Daleel 1980: 106-107, Hill 1972: 381-382). It is recorded that Bishop Hananya was the first Maronite Bishop in Cyprus. He arrived on the island c.1316 during the reign of the Lusignans (Gemayel 1992: 191, Daleel 1980: 107). Bishop Girgis, who attended the provincial council of Bishops held in Cyprus in 1340, succeeded him (Gemayel 1992: 191, Awwad 1950: 37). Bishop Youhanna (c. 1357), Bishop Jacob Al-Matrity (c. 1385) and Bishop Elias (c. 1431-1445), whose name was included in the working papers of the Council of Florence, and then Bishop Youssef (+ 1506) held this position successively (Daleel 1980: 107, Awwad 1950: 38). The Reign of the Venetians and the Onset of the Degeneration of the Maronite Colony in Cyprus (1489-1571) The reign of the Venetians (1489-1571) was very severe on the citizens of the island. They adopted a Western feudal system and imposed exorbitant taxes. The worst reign was that of Jacques II le Bâtard. His despotism caused a notable reduction in the island's population. Add to that the epidemics and the recurrent raids of the Muslims of Egypt, which ravaged the island from the fifteenth to the sixteenth centuries (Cirilli 1898: 13) and, in turn, caused further reduction in the population of the island (ibid. 1898: 13, McGuire1967: 568). The calamity that weakened the Maronite presence was brought on not only by the corrupt reign of the temporal rulers and governors of Cyprus, but also by the vile treatment of the Greek and Latin ecclesiastical authorities (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462). In fact, the treatment of the Maronites by some of the Latin rulers and clergy was unpredictable. At times they were protective, at other times they tried converting them to the Latin rite (Hill 1972 1077) and in other periods they were abusive. This behaviour prompted the intervention of the Maronite Patriarch whenever things got out of hand. For example, in 1514, the Maronite Patriarch Sham'oun al Hadthy wrote from his See in Qannoubine to Pope Leo X informing him that the Latin Bishop of Nicosia had confiscated the Saint John Maronite Church and its property and requested his intervention in favor of the Maronites (Assamarani 1979: 26-29). Furthermore, the Maronites who were under the ecclesiastical care of the Latin Church suffered the consequences of the moral decadence of the Latin clergy. According to Fabri who visited Cyprus in 1485, the Latin clergy were very ambitious, greedy and were buying and selling their episcopate (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462). The Greeks, who suffered immensely at the hands of the Catholic clergy and who had schismatic problems with the Maronites who were in union with Rome, were also persecuting the Maronites. This persecution led the Maronite Patriarch al Hadthy in 1518 to write a letter to Prince Albertos in Italy complaining of the injustice invoked by the Greeks over the Maronites, as well as protesting the Greek seizure of St. John Monastery in Kouzband. Similarly, in 1564, Patriarch Mousa Al 'Akkari wrote to Pope Pius IV requesting that His Holiness recommend the Maronites to the Venetians because the Greeks were restraining and insulting them (Assamarani 1979: 26-29). It should be noted that during the reign of the Latins in Cyprus (1191-1222), the Greek Orthodox Church hierarchy was subordinate to the Latin and was abused to the extent that the number of dioceses was reduced from 14 to 4 and all their schools were closed. This was caused by attempts of the Latin Church to convert the Greek Orthodox, using every means at their disposal, including force. Many Greek Orthodox fled Cyprus and those who stayed did nothing to participate in the defense of the island against the Ottomans, but instead welcomed with open arms their conquest of 1571 (McGuire 1967: 568-569; Palmieri 1905: cols. 2435-2436). During this era, the Maronites must have sustained many natural and man-made disasters, as evidenced by the fact that between 1224 and the Ottoman conquest of 1571, the number of their villages was reduced from 60 to 33 (Palmieri 1905: 2462). The reasons behind the degeneration of the Maronite presence in Cyprus could be many: the greed and oppression of the Latin Church; the Franciscan campaign to latinize the Maronites and their confiscation of Maronite churches; the persecution inflicted by the Greek Orthodox Church and their seizure of Maronite monasteries; the tyranny and barbarism of the Muslim invaders, plus the recurring natural and epidemic disasters (Cirilli 1898:12-13, Assamarani 1979: 25-29, 47). The Maronites remained shepherded ecclesiastically by their own Bishops. Bishop Maroun (1506), Bishop Gebrayel Al Kela'i (1505-1516), Bishop Antonios (1523), Bishop Girgis al Hadthy (1528), Bishop Elie Al Hadthy (+ 1530), Bishop Francis (+ 1562), Bishop Girgiss al Hadthy (1562-c.1566) and Bishop Julios (1567) held successively the title and position of Maronite Bishop of Cyprus (Daleel 1980: 108). The Cypriot Maronites under Ottoman Domination (1571-1878) Known in general as dhimmis or infidels, like other Christians, the Maronites were also called Suryani under the Ottomans (Jennings 1993: 132, 148-149). The Ottoman domination of Cyprus brought on the demise of the Maronite colony on the island. As their villages became depopulated through death, enslavement and migration, the Maronite population became almost extinct and, because of persecution and taxation, their bishops and archbishops became non-resident. While the Greeks did nothing during the Ottoman invasion, the Cypriot Maronites stood beside the Latins in their defense and saw the invasion of the island ruin their settlements. Soon after total Ottoman control over the island, the Ottomans recalled the allegiance of the Maronites to the Latins. Similarly, the Greeks remembered the oppression of the Catholics, and since most of the Catholics who had stayed on the island were Maronites, it was they who suffered retaliation. Together, the Ottomans and the Greek Orthodox inflicted the worst treatment on 'this unfortunate community' (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462; Cirilli 1898: 14-15). In 1572 the Maronites had 33 villages and their Bishop resided in the Monastery of Dali in the district of Carpasie (Palmieri 1905: col. 2462). During Ottoman rule, 14 Cypriot Maronite villages became extinct. By 1596, about 25 years after the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus, the total number of Maronite villages had been reduced to 19 (ibid. 1905: col. 2462, Dib 1971: 177). The Ottomans, after annexing Cyprus, imposed increasingly high taxation on the Maronites, accused them of treason, ravaged their harvests and abducted their wives and children into slavery (Cirilli 1898: 20). Many Maronites had died during the defense of the island, many more were either massacred or taken as slaves, many others dispersed throughout the island to escape persecution, and those who remained in their villages found themselves in a pitiable condition (Cirilli 1898: 14-15). Consequently, a group fled to Lebanon, another group accompanied the Venetians to Malta (Dib 1971: 177) and those who stayed behind "had to submit, in addition to the yoke of the conqueror, to that of the Greeks, which was no less troublesome" (ibid. 1971: 177). This treatment was the main reason why appointed Maronite clergy to Cyprus no longer resided on the island and preferred to stay in Lebanon. These atrocities were the most direct cause of the reduction in the Cypriot Maronite population and subsequently in the number of their villages. During this period, the Bishops who served the Maronites were Bishop Youssef (+1588) and Bishop Youhanna (1588-1596) (Daleel 1980: 108). While the Ottomans ruled, the Greeks, who had gained a bit of advantage for a while, began their retaliation against the Catholics –– which meant the Maronites, who were the only Catholics left on the island (Palmieri 1905: col. 2464). The vengeance of the Greeks began with the confiscation of the Maronite churches and was magnified by their accusation that the Maronite clergy was working for the return of Venetian rule to Cyprus and was plotting against the Ottoman Empire before the Sublime Porte in Istanbul. Consequently, the Ottomans inflicted their anger on the Maronites. They killed, exiled, imprisoned and enslaved many. They obliged many others to embrace the Greek Orthodox rite and to obey the Greek hierarchy. This persecution caused a considerable number of Christians, including a good number of Maronites, to adopt Islam as a survival mechanism (Cirilli 1898: 11, 21; Palmieri 1905: col. 2468). By 1636, the situation had become intolerable and the conversions to Islam began. "Since not everyone could stand the pressures of the new situation, those unable to resist converted to Islam and became crypto-Christians, mostly Armenians, Maronites and Albanians in the northern mountain range and along the north coast, particularly at Tellyria, Kambyli, Ayia Marina Skillouras, Platani and Kornokepos" (Jennings 1993: 367). The Maronites who adopted Islam were centered in Louroujina in the District of Nicosia and were called Linobambaci -- a composite Greek word that means men of linen and cotton (Palmieri 1905: col. 2468). However, these Maronite who had converted in despair did not fully denounce their Christian faith. They kept some beliefs and rituals, hoping to denounce their 'conversion' when the Ottomans left. For example, they baptized and confirmed their children according to Christian tradition, but administered circumcision in conformity with Islamic practices. They also gave their children two names, one Christian and one Muslim (Hackett 1901: 535; Palmieri 1905: cols. 2464, 2468). Father Célestin de Nunzio de Casalnuovo, a Franciscan from the Holy Land, worked for 33 years on returning the Linobambaci to their Christian religion. Some communities responded and asked him to establish schools in their villages. He obliged by opening two schools. But the Greek hierarchy continued to agitate the Muslim fanatics, who began attacking the Linobambaci and their agriculture fields. The Linobambaci, fearing for themselves, withdrew their religious aspirations and the whole re-conversion operation was halted (Palmieri 1905: col. 2468). Reverend Jérôme Dandini, the Envoy of Pope Clement VII, visited the Maronites of the island during his papal mission to the Maronites of Lebanon in 1596. Dandini stated that the Cypriot Maronites were all under the authority of the Maronite Patriarch whose See was in Lebanon. He also declared that at times there was at least one priest for each parish and that sometimes there were eight, like in Metoschi. He named the 19 Maronite villages left in Cyprus: Metoschi, Fludi, Santa Marina, Asomatos, Gambili, Karpasia, Kormakitis, Trimitia, Casapisani, Vono, Cibo, Ieri, Crusicida, Cesalauriso, Sotto Kruscida, Attalu, Cleipirio, Piscopia, Gastria. However, when he visited Cyprus in 1596, he learned that there were not many Maronite clergy left, that many Maronites had either fled or apostatized and that there were only ten parishes, the most important being Saint Marina, Cormakiti and Asomatos. He found the Maronites in a miserable situation (Dandini 1656: 23). Noting the poverty of the Maronite people, the lack of priests to serve their communities and the sad state of their parishes, Dandini recommended that the Maronite Patriarch send a bishop to serve the Maronites of Cyprus. In 1598, Father Moïse Anaisi of Akura was designated bishop and he stayed until 1614. He was followed by Girgis Maroun al Hidnani (1614-1634), who was a visiting bishop residing in Lebanon; Elias al Hidnani, who visited the Island at the request of the Patriarch in 1652; and Sarkis al Jamri al Hidnani (1662-1668), who lived in Nicosia (Daleel 1980: 108). Bishop Istephan Duwaihi, who was appointed bishop of Cyprus in 1668, became the Patriarch in 1670 and upon his enthronement assigned Father Luc, a native of Cyprus as the new bishop (1671-1673). Bishop Luc was the last bishop to live in Cyprus, (Daleel 1980: 108-109). After Bishop Luc’s death, no bishop resided on the island (Palmieri 1905: col. 2463; Cirilli 1898: 15-18). However, the Maronite bishops assigned to the See of Cyprus continued to visit the community on occasion. Bishop Boutros Doumit Makhlouf (1674) visited the island three times during his term. Bishop Youssef (1687) was the last bishop to visit the island in 1682 (Daleel 1980: 109). It is noted in the Franciscan archives in Nicosia that "Maronite villages were administered by Latin priests from 1690 to 1759, which shows that the Maronites lacked priests of their own rite. The view is commonly held that the Maronites were brought under the Orthodox bishops, under whom they remained until 1840, when, thanks chiefly to the efforts of the French Consul, they returned to the rule of the Maronite patriarch in the Lebanon…" (Hill 1972: 382). The Maronites of Cyprus were to wait until 1848, or 166 years, before their bishop visited them again. They were abandoned and left without any spiritual guidance of their own. Certain villages, such as Kitrea and Saint Raymond, adopted Islam. The rest were hunted and massacred by the Greeks who were given jurisdiction over them (Cirilli 1898: 18, Palmieri 1905: 2463). A very important event took place in 1735, when the Superior General Abbot Mekhayel Iskander al Ihdny of the Lebanese Maronite Order of monks made the decision to dispatch two monks -- Father Boutros al Mousawer and Father Makarios al 'Ashkouty -- to Cyprus to open a school for the children of the Maronite community on the island and to spiritually guide the faithful of the Church (Assamarani 1979: 95). The school was opened in 1736 and a monastery was built in Metoschi for Saint Elias (ibid. 1979: 95-97). However, the monastery was later confiscated by the Greeks and then completely destroyed in 1974 (ibid. 1979: 97-99). The Synod of Mount Lebanon, which occurred in 1736, reduced the number of dioceses but kept the Bishopric of Cyprus as one of the remaining eight. The jurisdiction of this Bishopric was not so clear, however, since it encompassed the island of Cyprus, as well as several villages and towns in the Kisserwan, Maten and Beirut districts of Lebanon (Gemayel 1992: 188). For security reasons, the Bishop of Cyprus resided in Lebanon after the Ottoman conquest of the island and was therefore granted authority over several villages in Lebanon in addition to all of Cyprus (ibid. 1992: 189). The letter of appointment of Bishop Salwan in 1892 confirmed, among other letters of appointment, the above facts. The letter reads in English: "… We have elevated our son the Priest Nimatullah Abi Salwan… to the sacred rank of Bishop and have made him Bishop over the city of Nicocia in the Island of Cyprus and the Church of Mar Shalita [Kornet Shehwan, Lebanon] its seat and have made him the legal shepherd of this diocese… on June 12, 1892… and have delegated to him the administration of the said diocese's spiritual and temporal affairs…" (Signed by His Beatitude the Patriarch Yohanna el-Hage and seven other Bishops) (Gemayel 1992: 189). It was only in 1988 that the See and residence of the Bishopric of Cyprus returned to the island and its jurisdiction was again exclusively that of the island (ibid. 1992: 191).

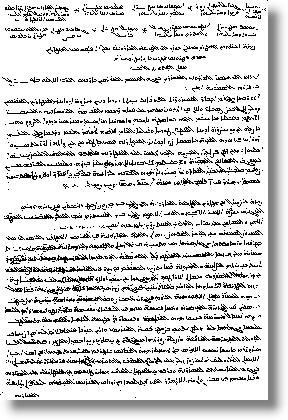

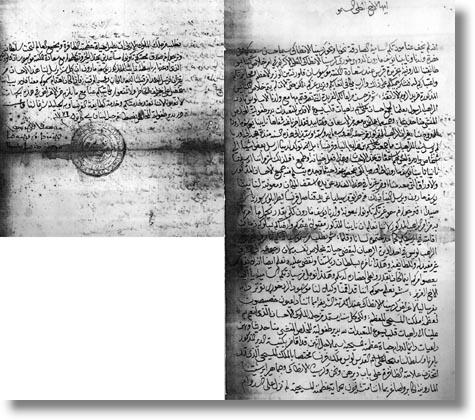

Under Ottoman rule and especially from 1750 onward, the Maronite Church in Cyprus was under the jurisdiction of the Greek Church, "all the Maronite churches in the villages are subject of the Greek Bishops of the dioceses in which they are situated, in accordance with the Sultan's berats; these Bishops grant them dispensations for marriage and divorce…" (Hill 1972: 382). The Greek bishops remained in control and persecuted the Maronites "even to the shedding of blood; Archbishop Chrysanthos and the Dragoman Hajigeorgiakis Kornesios left a bad name behind them" (ibid. 1972: 382). It was not until c. 1840 that the Maronite Patriarchate was successful in obtaining from the Sublime Porte a firman removing the Maronites from the rule of the Orthodox bishops and restoring them to the rule of the Maronite bishops. This resulted from the diplomatic efforts of Elias Efendi Hava, the Maronite Patriarch's representative in Constantinople, and the untiring labor of Mr. Toread, the French Consul in Cyprus (Cirilli 1898: 22-23, Hill 1972: 382). This decision facilitated the visits of the Maronite Bishops to their flock in Cyprus and it may have "led to a large increase in the number of professing Maronites" (Hill 1972: 383). In 1848, Monsignor Geagea made his first pastoral visit to the island. He then visited his flock in Cyprus in 1867, 1878 and 1879. His successor, Joseph Zogbi, visited Cyprus twice. In 1893 the new bishop, Monsignor Nemtallah Salwan, visited his parishioners on the island a year after his enthronement. Throughout the Ottoman reign, the Maronites attempted through diplomatic channels, both religious and secular, to alleviate the suffering inflicted upon them. For example, in 1845 the Maronite Patriarch wrote to the Sublime Porte requesting that the Maronites be removed from the oppression of the Greek clergy, be authorized to constitute an independent church and be put under the jurisdiction of the Maronite Bishop of Cyprus (Palmieri 1905: col. 2463). In 1686 a group of Cypriot Maronites paid a visit to the Ambassador of France in Istanbul. They had four requests -- the payment of property taxes only by the 150 residents who remained in the villages but not for those who no longer resided there; the exemption of bishops and priests from property tax and capitation payment (jaziyat); the cessation of the Greek bishop's guardianship over the Maronite churches; and the freedom to celebrate the Maronite liturgical rite rather than the Greek (Assamarani 1979: 41-47). The French Ambassador to Istanbul, Mr. Gerardine, in July 1686 obtained four orders or firmans from the Sublime Porte to benefit the Maronites. (Assamarani 1979: 42-43). These firmans, however, made only a temporary impact, for the Greeks went back to their old ways of persecuting the Maronites and confiscating their religious properties (ibid. 1979: 44). In 1756, the Maronite bishops presented to the French Ambassador in Constantinople a petition describing the confiscation by the Greek Orthodox Bishop of two Maronite churches -- Our Lady in Kafriat and St. Antonios of the Naher. The report requested a firman ordering that these churches be returned to the Maronites. The petition carried the signatures of six bishops (Bkerke, Vol. II, pp. 366-367, Assamarani 1979: 44-45). Following this, several other letters as well as a patriarchal envoy, Father Youssef Maroun Duwaihi, were sent to Cyprus, but none of these efforts resulted in the return of the churches to Maronite authority (Bkerke, Drawer of Patriarch Youssef Istephan # 164, Assamarani 1979: 46).

The customary Ottoman sources for detailed population registration in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are severely lacking for Cyprus. The total population of the island was estimated to have been 90,000 in 1824-1829 (Hill 1972: 33). -- "In 1841, the Governor Talaat Efendi put the total population [of the island] at 108,000-110,000, of whom 75,000-76,000 were Greeks, 32,000-33,000 Turks, 1200-1300 Maronites, 500 Roman Catholics (mostly European), and 150-160 Armenians" (ibid. 1972: 33). However, in the census of 1891, the Maronites were estimated at 1,131 out of 209,286 Cypriots and were mostly in four villages (Hill 1972: 383, Hackett 1901: 528). The most important document available regarding the Maronites of Cyprus in the Ottoman era is that of Bkerke, Vol. II, page 504 which was written by the Priest Bartelmaous Iskandar Al Ghabri to the Bishop of Cyprus Elias Gemayel in 1776. In this document, which reads like a report on the situation of the Maronites in the island, Al Ghabri gives detailed estimates of the name of the Maronite villages, the name and number of the churches, the parishioners and priests, as well as the waqf or pious endowment of each parish. He estimates that the number of the Maronites is 503 in 11 villages (Bkerke, Vol. II, page 504, Assamarani 1979: 50-52).

The Bishop of Cyprus, although residing in Lebanon, always carried the title and responsibility of the Maronites of Cyprus. Three of the bishops who held this position during Ottoman rule were elected Patriarchs over the whole Maronite nation -- Bishop Estephan Dwaihi elected in 1670; Bishop Toubia el Khazen elected in 1756; and Bishop Philibos Gemayel the Second elected in 1795 (Gemayel 1992: 192-193, Assamarani 1979: 112-132).

In summary, the Maronites were a distinct community in Cyprus ever since the twelfth century. Their settlements numbered 60 in 1224; 23 in 1570; 19 in 1596; 10 in 1776, and 4 in 1878. The regression of the Maronite colony in Cyprus began with the Latin reign and received its final blow under Ottoman rule. Their life on the island was filled with sorrow and pain. However, they maintained a presence and persisted in their faith, although some succumbed due to persecution. They had their own clergy and bishops, but effectively they were under the ecclesiastical domination of either the Greeks or the Latins. In Cyprus the Maronites faced 'Latinization', Greek schismatic abuse, and 'Islamization'. What remains now are only four Maronite villages, Kormakitis, Karpasia,

Asomatos and Agia Marina. Their populations have been largely displaced

due to the 1974 Turkish invasion and partition of the island. The four

villages, which are practically unpopulated but for a few elderly persons,

are all located in the Turkish divide of the island and are facing annihilation

because of the laws imposed on the right of return and the right of land

ownership.

Bibliography Assamarani, Ph. Al Mawarinat fi Jazirat Koubros, (Beirut 1979) Cirilli, J. Les Maronites de Chypre, (Cyprus 1898) Dandini, J. Missione Apostolica al Patriarca e Maroniti el Monte Libane, e sua Pellegrinazione a Gierusalemme, (Cesena 1656) Dib, P. History of the Maronite Church, Translated by Seely Beggiani, (Detroit 1971) Duwaihi, I. Tarikh al Azminat, Ed. B. Fahd, Publisher Lahd Khater, (Beirut n.d.) Daleel Abrashiat Kobros al Marouniat fi Lubnan wa al Jazirat (Directory of the Maronite Diocese of Cyprus in Lebanon and the Island), (Antelias 1980) Emilianidès, A. Histoire de Chypre, (Paris 1962) Gennings, R. The Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World 1571-1640, (New York and London 1993) Gemayel, B. The Diocese of Cyprus, Al-Manarat, Year 33, No 1 (Beirut 1992) Hackett, A. History of the Orthodox Church of Cyprus, (London 1901) Hill, G. A History of Cyprus, Vol. 1-4, (Cambridge 1972) Leroy, J. Les Manuscrits Syriaques A peintures Conservés dans les Bibliothèques D'Europe et d'Orient, (Paris, 1964) Mc Guire, M. Cyprus, New Catholic Encyclopaedia, vol. IV, (Washington D.C. 1967) Plamieri, A. Chypre, Dictionnaire de Théologie Catholique, Tome II, (Paris 1905) |