Part III By Sri Kuhns* In this section of the Journal of Maronite Studies (JMS), we bring you travel accounts of past and current travelers who have written about the Maronites and their environments. These accounts are unedited and represent the views of their author(s). Saturday, Aboona (Father) Marwan Tabet and his assistant Rosemary Richie, an English teacher from Texas, came by to pick up Guita and me. I was surprised to see how young Aboona was-- thirty-five years old. Although he was very busy, he still made time to take us to the Kraime Monastery in Ghosta. The monastery belongs to the Order of Lebanese Missionaries (OLM), an order of monks to which Fr. Tabet belongs. From the monastery, you may catch a view of the Mediterranean by looking through the opening between the two hills which frame the monastery grounds and the rest of the valley leading to the sea. Its structure is old and was probably built at least four centuries ago of carved yellow stone. Cultivated fields surrounded it. Fr. Marwan told us that, as a seminarian, one of his duties was to farm the land and plant trees and vegetables. He said that this made him more attached to the land of his ancestors. It was then that he understood the mysticism of Eastern monasticism's life of prayer plus work in the fields.

Upon our arrival, Father Philip El-Hage Souaibi, the Superior of the Monastery, and several other monks greeted us. We had delicious coffee and pleasant conversation in the reception room in which are displayed old, now antique, instruments and artifacts. Before lunch, the Superior gave us a tour of the monastery. He opened a closet with a glass door to show us the founder’s vestments. Embroidered in gold, they were presented to him as a gift from the Vatican upon his enthronement as a Bishop. The Superior said that the vestments had been worn only once. Being monastic, the founder preferred the simple habit of a monk. I also saw ancient pottery containers for wine, oil, and preserved meats and vegetables. A more fascinating object was a stamp used for embossing religious symbols on the eucharistic bread.

The Superior then led us to the dining room for lunch. Six monks and four seminarians stood in silence behind their chairs. After Father Superior blessed the food, we sat down to eat. Our lunch consisted of stuffed cabbage with garlic and mint, yogurt salad with fresh cucumbers, scalloped veal, hommos, green olives and mixed pickled vegetables. For desert we had an exquisite Kharroob dip-- molasses and sesame cream-- followed by fresh fruit. The silence was broken when the Superior introduced the four brother-seminarians from Australia. They were young and handsome. With my great curiosity, I asked them why they wanted to become monks and why they were in Lebanon. They explained that the monastic life is their religious calling and that they are studying at the mother-house of the OLM order in Lebanon before returning to serve in Australia. I pressed the question even further: Why a Maronite order? One said that although his father was Christian, neither Maronite nor Lebanese, it was his mother who had installed a great love for the Maronite faith and for Lebanon, the spiritual and temporal land of his Maronite heritage. Others described themselves as 'bred in the bone’ Maronites who cherish their birthright. After dessert and our prayer of thanksgiving, we went with the Superior and some of the monks to see the church of the Holy Trinity. There we saw an antique painting, which depicts the Trinity, adorning the wall above the altar. It represents God the Father as a benevolent, old man with outstretched arms, and the Holy Spirit as a white dove with outstretched wings, while both simultaneously embrace and support the beloved Son nailed to the cross.

After praying with the monks, we thanked them for their kindness and took our leave. Aboona Marwan drove us back to the dormitory where we were to spend the night. Upon our arrival, Guita called her parents. She read my quickly scribbled note telling them that I missed them and she told me that they, coincidentally, were saying that they missed me terribly. The dormitory was comfortable and had hot and cold running water. Two twin beds were in the room which Guita and I shared. We could look out into the school yard and observe the students dressed in uniforms. They were in orderly lines as they entered the classrooms. The Sisters of the Maronite Holy Family Order run this elementary school. After napping, we were invited to share with Fr. Tabet dinner prepared by the nuns. We were greeted by Sister Roger Azar and Sister Mariette Yahyeyan, the Principal. We sat down to get acquainted and then had dinner served by the nuns and two girls from Kfarhayy. The lentil soup, chicken, cheese, olives, and baklava and fruit were all delicious. The nuns engaged us in cheerful conversation throughout the meal. They were relaxed in the presence of Father Tabet. I learned later that his order and theirs are twin organizations and they have known him since he was a seminarian. Because it was a very cold night, Guita and I requested Zhourat (herbal tea) instead of coffee. The nuns were eager to make us comfortable and keep us entertained. While watching the news on TV, I used the word 'Barrid' which means ‘it is cold.’ In the blink of an eye, Sister Yahyahan placed a black cardigan over my shoulders and said that it was for me to keep. Spontaneously, I cried out: You have earned your place in heaven, for by feeding me, you have fed Christ; and by clothing me, you have clothed Him. You have fulfilled the Bible’s teachings. Both nuns smiled and gave me a hug. When they noticed that I was wearing summer sandals, they brought me a pair of shoes. I thanked them and explained that I can not wear anything but open sandals even in the winter. Guita’s father Georges had warned me about the cold weather and earlier had offered to buy me warm shoes. While sipping my tea, my mind struggled to comprehend the genuine concern and generosity of these Maronite nuns. Guita had told me when we were in Washington, D.C., that, in Eastern tradition, true Christian giving is not when you give after your own needs have been met, but when you yourself are still needy and give of what little you have-- the widow's mite! While watching the news in the dormitory, I met a young girl named Guita Joseph Khoury from Bkerkacha. She invited me to visit her lovely village if I ever return to Lebanon. On Sunday morning, Guita and I prepared for our visit to Blessed Rafqa (Rebecca). Jacques and Claudia with their five-year-old daughter Rachel picked us up. We greeted each other like long lost relatives. Guita was asked to sit in the front so Claudia and I could sit in the back with little Rachel who had drawn a picture for me. We soon stopped at al-Dwaihi Pastry Shop where Jacques treated us all to a wonderful breakfast of Kanafeh. This consists of a special pocket-bread baked with sesame seeds and then stuffed with hot melted cheese; a thin layer of cream of wheat mixed with orange and rose blossom water is added and all of this eastern delight is drizzled with honeyed syrup. I know why it is a favorite breakfast-- it is truly divine! On our way, we passed through a lower range of mountains which filled the horizon. Bushes with multicolored flowers resembling a beautiful Persian tapestry spread before us. There were orange and olive groves on either side of the road. I wish one day to walk these mountains, listen to God, and be quiet within myself. Many of the paths are steep and difficult to climb. Gigantic boulders, too light for limestone and too dark for marble, protruded from the soil here and there. The quarries have scarred the mountain and the land has not been restored to its former condition. The villages we passed seemed to be at peace. Bells rang everywhere as parishioners mixed with pilgrims. Some, with rosaries in their hands, walked to church. What a life! I was envious. We arrived in Jrabta and went to the church at Saint Joseph’s Convent. It was celebrating the one hundred year anniversary of its founding and was filled with people. A monk celebrated mass and a choir of the convent nuns intoned the chants and sang the hymns in Syriac (a dialect of Aramaic which Jesus spoke) and Arabic. Their voices were heavenly. Five young novices in distinctive habits were there, too. All the people, young and old, men and women, knew the hymns and prayers by heart and actively participated in the liturgy. When we asked for a guide, Sister Marie Keirouz Basile from Smar-Jbeil took us under her care and invited us for coffee and candy. We met Father Hanna Alfred Wehbe from 'Amsheet. While the rest were talking with Father, Sister Basile told me that the plaque above the door leading to the convent’s courtyard warned that the cloister was straight ahead and was not open to the public. She explained that the nuns of this convent, after two hundred years in the cloister, had been compelled to leave their sanctuary --'to re-enter the world'-- in order to serve and alleviate the suffering of their people who had been devastated by the war (1975-1990). The angelic face of Sister Basile entranced me. She looked happy, loving and at peace. Her smile alone could restore health to the sick and hope to the despairing. She was young and beautiful in her black habit. She wore her ring of commitment to Christ on her right hand. I respectfully asked to take her picture, but she blushed, bowed her head, and stepped away backwards. We all begged her and she finally accepted graciously.

Sister Basile took us to the tomb of Blessed Rafqa. It was constructed of marble to resemble a ship with a Cross on its bow. We said a prayer and went to the very place in the room where she suffered her agony. It was during the last part of the 19th century, when the simple girl Rafqa, seeing the oppression and suffering forced upon the Christians of Lebanon, prayed and begged Christ her Bridegroom to allow her to bear some of His suffering and grief over the plight of His people. Her wish was granted immediately. She became blind, lost all muscle control, and became totally disabled and dependent. I was told that never once during the rest of her lifetime of suffering and prayer did she complain.

The traction-like apparatus which in life had supported and contained her disjointed, skeletal body still hangs from the hook anchored in the ceiling of her bedroom. As we continued our pilgrimage to a garden in which stood a statue of Blessed Rafqa, we read a plaque nearby which states "Do not leave this place until you cleanse your heart by confessing your sins." I sat down on a rock and did just that.

Before we left to visit the Monastery of Saints Cyprian and Justina (Saints Kebrianos and Youstina) in Kfifan, I collected more wild flowers and scooped up a handful of sand which is associated with miracles attributed to Blessed Rafqa. Sand in the arid regions of the East may be considered a substitute for-- and symbolic of-- water. Grains of sand and drops of water-- like the religiously significant water from the miraculous spring at Lourdes, the water from the Qadisha river valley in North Lebanon, and water from the Jordan River-- are just two of many valid instruments through which Christian miracles are performed. If we but ponder a moment, we will recognize the sacramental worth and the powerful imagery of Semitic and Christian symbols-- oil, incense, bread, wine, water, ashes, and even the grain of sand. I felt that I was walking on air, and so it was, for I was in heaven. At the Monastery of Kfifan, we visited the tomb of the Honored Neemtallah Al-Hardini (1808-1858), through whose intercession were attributed many miraculous cures. He had lived as a hermit at ‘Annaya and was a friend and contemporary of Saint Sharbel. At the Monastery we met a dignified monk with an angelic smile. He introduced himself as Father Joseph Peter Al-Sha’ar, a monk of the Lebanese Maronite Order. With his black habit and cowl and his long white beard, he resembled Saint Sharbel to a haunting degree. He is fluent in six languages and on the tour he told us in English the story of the Honored Hardini. He photocopied part of the history of the Monastery and of Hardini’s life.

We were served coffee and sweet wine produced by the monks. This is the same wine used during mass. The room in which we sat contained glass bookcases filled with antique books in Syriac and Karshuni (Arabic written in Syriac letters that was invented as a medium of communication among the Maronites but not understood by Muslims). Pictures of the organizers of the Order hung on the wall. Agricultural implements no longer in use hung on an opposite wall. To my surprise, there was a Xerox machine in one corner of the room. The contrast was unbelievable: a building made of rocks by the monks many centuries ago and a photocopier! While sipping the coffee and savoring the 'divine' wine, I asked the benevolent Father Al-Sha’ar if there would be a room available should I come back to spend a year in contemplation and writing. His face shone radiant as he lowered his eyes from my gaze, smiled and said: "If there isn't room, I have a place for you in my heart next to Jesus and Mary.' His sentence is one of the treasures that I have collected. Those monks who imitate Christ’s life in their monasteries love us just as He does. What true Christianity this is! Afterwards, we visited the three Basbous brothers who are sculptors in the village of Rashana. From various types of rock, they have created works of art which adorn the village. The garden in front of their studio resembles an open gallery of statues. It is an eclectic collection of the sacred and the profane. The studio produces works of sculpture in both the classic and the modern style. One of the brothers exhibited his works at the invitation of the Indonesian government and one of his sculptures stands in the museum in Jakarta. I was pleasantly surprised and promised that on my next trip to Indonesia, I would visit the museum to see that work of art.

Tired and hungry, we telephoned Therese and told her that we were on our way home. Neither she nor Georges had eaten because they wanted to eat dinner with us. This was typical behavior of these loving people-- so thoughtful, so considerate. After the late lunch and a nap, Marie Khalife and her sister Therese came by to take us on a unplanned short trip. We drove up to the mountain village of Deek-el-Mahde, where an architect had built for the children of the area the second largest nativity scene in the world. The scene was displayed in the parking lot of the Church of St. Elias. The Christmas scene was one of wonder with flowing rivers, a snoring Santa, cheerful music playing and ever so much more. The children were in heaven. Admission was free and it was open and visited by Lebanese of every religion. On my way out, I thought to myself that love combined with skill can create the unbelievable. Our surprise was a bookstore in Antelias. Guita, who loves books, and I had a field day rummaging through and searching out rare and out of print books. The place was closed because it was eight o'clock, and just as Marie predicted, the owner was having his coffee across the street at the coffee shop. He came over and happily opened the store for us. Inside, the books were stacked one on the top of the other. It was difficult knowing what he had available. However, I found what I wanted—the complete collection of Gibran Khalil Gibran's work, bound in green leather and inscribed in gold Arabic letters. The collection consisted of 11 volumes and cost me $40.00. The owner, Mr. Hanna, decided to take us to his new but unfinished bookstore where the books are displayed on shelves, and arranged by subject to make it easy for the customers. We spent another two hours there. Everybody bought books and chatted with Mr. Hanna, who is a confirmed bachelor. We laughed hard at the sight of Marie bargaining with him on the price of some books. My Gibran collection felt so heavy, that upon entering the house, I told Thérèse to keep the books for me and that someday I would return for them. She answered saying with a smile: 'You will always be welcome'. I could not believe that a week had gone by since my arrival in Lebanon. It felt like I had traveled the world over because I had seen and experienced so much. In three days, I must depart for home. Monday, February 24, 1997. It was a beautiful, sunny day. We were dressed up to meet Ms. Helen Khal, Guita’s American friend of Lebanese descent, who lived and worked most of her life in Washington, D.C. Helen is a painter, an art teacher, a writer, and an editor. She studied at the Beaux Arts university in Lebanon about fifty years ago. She decided to retire in Lebanon to paint and teach. Marie drove us to the exclusive area of Rabieh where Ms. Khal is staying with friends. The villas of this area are a blend of Lebanese and European architecture, with outstanding gardens and a breathtaking view of the sea. We visited Ms. Khal at the home of her friends Mr. and Mrs. Nammour. At the entrance, the garden looked lovely with sculptures, by famous artists, positioned everywhere with artistic taste. Inside, several paintings by Ms. Khal and other renowned Lebanese, Middle Eastern and international artists covered the villa walls. As we sat to visit, Mrs. Nammour announced that we must stay for lunch. Mr. Nammour had already phoned and insisted on us having lunch with them. Jihad, the son, was home too. He is a student at Saint Joseph University in Beirut and editor of the University’s student newsletter. He is very intelligent, patriotic, polite, and speaks fluent English. When Mr. Nammour arrived, we continued talking politics and a debate broke out between Jihad and his father. I enjoyed watching them challenge one another with arguments and ideas flying back and forth. I was thinking about the difference in mentality between the generations in Lebanon and the war’s effect on the thinking of both. Mr. Nammour appeared thankful when the maid called us to lunch because he wanted to drop the subject. Mr. Nammour broke bread with me and talked about Alita, his new development whose urban design includes parks, side walks, an artificial lake, and a small chapel for Saint Sharbel. After lunch, Mrs. Nammour showed me her orchids for she loves to garden just as I do. We bade everyone good-bye, and left carrying with us a wonderful feeling of their hospitality and friendship. Personally, I was grateful for this new friendship.

Marie drove us back to the dormitory and thanked Guita for the lovely day. That evening, Guita, Rosemary and I took a walk and window-shopped in the Kaslik area. We hailed a cab whose driver, George Hanna, was a displaced Christian from the North. He drove slowly through the rain and said that he had had a bad day. Guita asked him to take us to a Lebanese restaurant. He kindly suggested a place for dinner where everything is home cooking. Guita mentioned Arak and he responded that she should sample his homemade vintage. He invited us to his home to taste the Arak. At his house, we met his wife Saide and his daughter Mirna, a law student. Mr. Hanna is dedicated to his family. His wife said that they are just as in love today as they were when they got married in 1967. While Mrs. Hanna offered us coffee, bananas, oranges, and her home-made sweets, Mr. Hanna disappeared to shave and change clothes. Guita had hired him to chauffeur us for the rest of the evening and to drive us to the dormitory afterwards. Before we left his house, Guita bought a gallon of his Arak for $65.00. Unfortunately, the restaurant recommended by Mr. Hanna was closed on Monday as are most restaurants. Nearby, we found Khaymet Abu Samir, where the specialty is fish. Looking out on the rain and the sea, we enjoyed the mezzeh --dishes of appetizers-- and a delicious grilled fresh fish called Lou'os and drank the Arak made by Mr. Hanna. Back in the dorm, I missed Thérèse and Georges my hosts and wished that I were back in my room at their house.

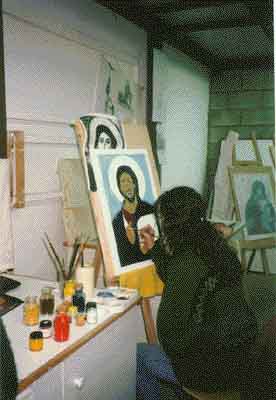

Tuesday morning, February 25. Fr. Tabet called to inform us that he was waiting downstairs to take us to Holy Spirit University. There we met Fr. Karam Rizk, the Director of the Institute of History. He escorted us to the Centre du Patrimoine (Community Center). It is a huge hall with antique pottery, archaeological artifacts, coins, the personal papers of Youssef el-Saouda who was one of the political thinkers of modern Lebanon, etc. There I saw the icon of Our Lady of Ilige which was recently restored to its 10th century condition. Fr. Rizk explained that the center is not yet finished, and that work on identifying, labeling and cataloging the collection is in progress. From the Center we went to the Institute of Sacred Art at the same university. Here, students are taught to paint icons, make stained-glass windows, do work in mosaics, and make religious vestments. In the patio of the Institute stood the famous Statue of Martyrs which adorned the main square in Beirut before the war. The Institute won the bid to repair the war-damaged statue. The sight of the statue will forever be imprinted on my mind for it is so symbolic of the recent Lebanese ordeal-- so true of this country’s past and possibly its future. The government decided to leave some of the holes in the statue as a reminder of the ugly war that swept through the country for over fifteen years.

We went back to the College des Apotres. There, I sat on the verandah under an oak tree, looking at Our Lady of Lebanon Basilica, thinking about my trip, the people I had met, the imprint left on Lebanon by this war, and impressed by the strength of these Maronites. What a lesson I have learned—one which cannot be taught in class nor at any university! In the evening, we were invited to the convent by the nuns because Fr. Elie Madi’s was going to cook-up his famed shrimp and spaghetti for us. The sisters greeted us with hugs and warm welcomes. Besides the appetizers, there was spaghetti, salad, cheese, and baked fish. Fr. Madi had studied in Rome for seven years and so I asked him to show me the proper Italian way to eat pasta. He was so happy to do so. When I found out that the fish was Lou’os, I just had to eat a small one because it is probably one of the best fish in the world. That night, Fr. Tabet drove us back to Jal-el-Dib where Thérèse was waiting to greet us. I was very happy to have come home and to sleep again in my own room. Tomorrow will be my last day in Lebanon and I want so very much to spend it at home with the Hourani family. The next morning, Thérèse prepared a wonderful breakfast for Guita and me. We sat around the coffee table and had some coffee. Thérèse asked if I would carry some specially prepared food for Madonna and Mashhour and I joked that I must share it with them. With a sweet smile she answered: 'Most certainly!' Thérèse had made Kibbe, a ground beef mixture with cracked wheat, onion and many spices, which she then made into egg shapes and stuffed with sautéed onion and pine nuts. It is a delicious Lebanese delicacy. Throughout my last day in Lebanon, people visited to tell me good-bye. The Srours came and gave me as a gift a hand-painted pot designed by Claudia. Marie came with several of her hand- made ceramic pieces with Lebanese motifs. Guita's cousin Gaby and his family brought me a beautiful mirror with a scene of Baalbeck, my name in gorgeous Arabic calligraphy, and my arrival and departure dates all carved by Gaby. All the gifts were meaningful if only for the fact that they were all hand-made specially for me and were given to me by my Maronite friends. I wrapped the gifts carefully so that they would reach America safely. My last night in Lebanon was an agonizing night. Though I wanted to be with my children again, I knew that I was going to miss the friends I had made here. I felt sad and nervous because I now felt really ambivalent about leaving. In the morning, George and I drank coffee together until it was time to leave. I felt sad to be leaving him while he was still sick. Then, Guita, Thérèse and I went to the airport. We said very little because I do not like good-byes and I hugged each of them and rushed into the airport. The processing was easy and the plane left at 8:30 am. After five hours of flying, I was back in Paris carrying the Kibbe for Madonna. In Paris, I called Madonna who was waiting for me and told her that I was on my way to her apartment. When I gave her the Kibbe and after she tasted one, tears came to her eyes --it was nostalgia for family and country. Madonna and I spent the rest of the afternoon talking about my trip and her family. Then, we went out for dinner to have my favorite French dish, Moules et Frites (mussels and French Fries). During the rest of my stay in Paris, I visited Madonna and took walks through town. The night before I left, she helped me pack and gave me a lovely fabric for a suit or a dress. On Saturday March 1, I flew back from Paris to Washington, D.C. Throughout the flight, I did not utter one word. I was reliving the whole trip in my mind. My children met me at the airport with flowers. When we were home eating dinner, I told them about my trip and gave them their gifts. We all were very happy! A few days later, I went to the Smithsonian museum as I often do. At an exhibit of plants and perfumes, I spotted some antique bottles and jars on a high wooden rack. Inexplicably, my eyes fell upon a rare porcelain blue jar upon which appeared one word: Byblos! If I had seen this a month ago, it would have meant nothing. Now it means so much. I am forever transformed by my experience among the Maronite people. How can I not be? Once again I had parents, Thérèse and Georges. I had renewed my Christian faith. I was again reminded of the need to love others unconditionally, to stand firm in my beliefs, to share what I have and perhaps -- at some time -- to give all, even my life. The Maronite people are the living Bible. Not one person, lay or clergy, preached the Bible to me. Not once! Not one person mentioned religion, even when I visited monasteries and convents. But they all taught me about Christ and the Bible by their deeds, their love for their families, their hard work, their acceptance of God's will. Discourse on religion was not necessary for they showed me their Christian faith by their concern for me, by giving me a sweater to warm my body and a pair of shoes to cover my feet, by inviting me to their homes and feeding me from the abundance of their generous hearts. I felt at peace with them. I was not pressured nor was I judged. I respected their faith and tradition. I knelt and prayed to Mary, the Mother of God, I received the Eucharist, and I celebrated with them their love for Christ and their belief in His promised salvation. I am forever transformed by my journey among them. A week after my return, I asked my son Robert to buy me a Japanese flowering cherry tree. He came back with an 8-foot pink-flowering Kwanzan. The whole family gathered for the planting ritual. My eldest daughter Lani dug the hole and my two other daughters, Cita and Addie, planted the tree. This tree will grow to about 10 feet and it will have double pink flowers in the spring. My children and I planted the tree in the driveway of our house to commemorate my friendship with the Maronites, young and old, wherever they may be. This tree is a symbol of my gratitude for the generosity, love, and acceptance I felt throughout my visits among them, whether in Paris or in Lebanon. I am already planning my next trip. The mountains and valleys are calling me. The many sites I could not visit are waiting for me. *Sri Sadeli Kuhns is a writer and cultural observer living in Maryland, the United States of America. |